100 Stories

Little Ninoshima: No Such Thing as Nothing

Hiroshima is a place where one can meet people from all walks of life, each with a vastly different story to tell. Most of the locals were born and raised in this very city, or at least, another part of the prefecture, whereas others may hail from other corners of Japan. Regardless of birthplace, however, one inevitable topic that arises when meeting someone for the first time is that of one’s hometown. People tend to not only want to know where somebody is from, but also what kind of a place that is, according to the people who have lived there. I just so happen to be one of those curious souls who wants to know as much as I can about people’s hometowns, usually because it could provide a lead on my next exciting excursion.

“Did you grow up here in Hiroshima?” I might ask a new acquaintance.

“My family actually lives in Sera, but I moved here for college, and then got a job in the city.”

“Ooh, Sera. I’ve heard about that place. What’s there to see there?”

“Pretty much nothing,” is a reply that I hear all too often.

It’s a regrettable response, not because it’s uninteresting, but rather because it’s untrue. It’s physically impossible for a place to have absolutely nothing, so anyone who answers with, “nothing,” wasn’t thinking hard enough. Every place in the world, urban or rural, can pride itself on something, and in some cases, perhaps it takes an outsider to see the beauty of a certain hometown. After hearing about there being “nothing” in Sera, I got this desire to go there myself in order to confirm that there were indeed things to do, of which I found plenty.

Recently, I was conversing with a friend about obscure sites in Hiroshima City when the conversation shifted towards Ninoshima, a tiny island off the coast of Ujina Port. It’s a twenty-minute boat ride away and there are regular ferry services, but when I asked what there is to do, once again, the answer was, “nothing.” It’s a rather ridiculous response in the age of the Internet when we can readily look up stuff to do and see in the blink of an eye, but believe it or not, even when I looked up activities and points of interest on Ninoshima, even travel blogs were saying, “there’s nothing there.” Let me tell you something: islands in Japan are typically mountainous, so islands mean mountains, mountains mean trails, and trails mean hiking. In my eyes, Ninoshima already had one thing going for it from the get-go, and after my friend brought up a pool and elementary schools that aren’t overcrowded like the ones in Ujina, my interest was piqued.

I picked a day to visit, hopped on a streetcar (the number 1 or 3 from downtown; the number 1 or 5 from Hiroshima Station) bound for Hiroshima Port early in the morning, bought a round-trip ferry ticket on site (there’s a small discount for buying two trips at once), and made haste for the next departing ferry. Ninoshima is chock full of history and nature, and from those two fields sprout an array of experiences to be enjoyed on this sparsely populated island. So much so, in fact, that right after getting off the ferry, visitors will come across a tourist information center providing details on all there is to do around the island, as well as offering a few experiences that can be done on site. Visitors can rent a bicycle for the day, rent or purchase fishing gear, inquire about and book kayaking tours, buy some Baumkuchen, and even try their hand at making their very own Baumkuchen, which I opted to do (reservations are not required, but highly encouraged). If none of the above interests you, at least stop by to have a chat and fill out a survey, after which all visitors are offered a free cup of coffee or tea.

Making History

The name “Baumkuchen” literally means “tree cake” because it’s shaped like a tree trunk, and the exterior may resemble bark. This delicacy has its origins in Germany, but the first Baumkuchen in Japan was crafted on Ninoshima by a baker named Karl Juchheim, who initially sold confections such as Baumkuchen in Qingdao, China (the German equivalent of Hong Kong). Mr. Juchheim was captured by the Japanese in World War I and imprisoned on this miniscule isle, where he began to bake for his fellow inmates. Baumkuchen proved to be such a hit that his recipe soon became sold at the Hiroshima Industrial Promotion Hall (now the Atomic Bomb Dome). This incident was one of a series that sparked a deepening in German-Japanese relations, and is a significant historical account for an island that supposedly has “nothing.”

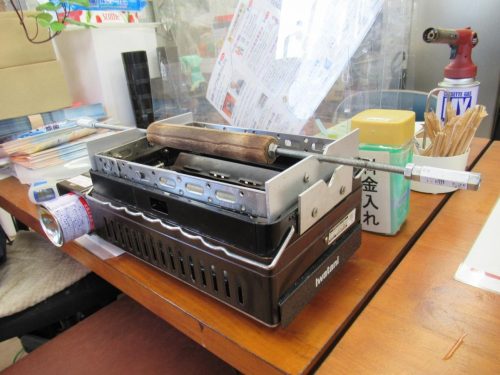

When I entered the tourist information center, the man inside was expecting me, and had already assembled a range for baking my Baumkuchen, as well as all the cookware and ingredients necessary to prepare the batter. There was also a document on the table outlining the steps for making Baumkuchen, and after the man gave a short history lesson about the dessert’s connection to Ninoshima, we got cooking. First, I cracked open the eggs and meticulously separated the egg whites from the yolks, pouring them into separate mixing bowls. From there, I would beat the egg whites with an egg beater on high power until the gooey liquid turned into a fluffy, white meringue spread.

Next was the bowl of egg yolks, which I also beat on high power whilst mixing in sugar, melted butter, and flour. The man mostly instructed me as I went through all the steps, but for the sake of photography, I had him take the wheel a couple times. After all that was done, I scooped the meringue into the bowl of egg yolk solution and stirred thoroughly until the liquid was uniform. The result below was the batter that would become my Baumkuchen (and my second breakfast at that)!

The man fired up the range and sprayed some edible lubricant onto the wooden rod, and explained how to cook the cake batter, layer by layer. As can be seen from the video below, adding the batter to the rod and letting it dry over the fire is a simple but long and drawn-out process. Between all the scoops of batter that can be drizzled onto the rod (much of which falls back into the mixing bowl), this action can be repeated for well over an hour, so make sure you’ve left your morning open and your plans on Ninoshima flexible. I might’ve been slower than the average participant, but it took me around an hour and a half to cook all the batter. When I was close to using it all up, I was tempted to keep drizzling to the last drop, but I was warned that uneven distribution of batter over the cylinder would lead to a rough and bumpy exterior, so I had no choice but to call it quits with a bit of delicious batter still in the bowl.

Baumkuchen, cut the edges off, that slipped the cake off the wooden rod, albeit with a little bit of a struggle.

halves in half and put the four pieces in a paper bowl for me to eat on the spot. I had originally planned on taking it with me as I trekked around the island, but he talked me into eating it at the table while it was piping hot, and boy, was I glad I took his advice! It was already hard to resist eating as I was baking it, so I hastily sanitized my hands and dug in. Guten Appetit!

Moment of Joy: Take the Cake

My finished product was indeed a beaut, and I was beyond proud of my own creation, which ended up resembling an actual tree trunk with its gradation of brown and lumpy, uneven surface area. I’ve had Baumkuchen in the past, sold pre-sliced in small packages all over Hiroshima City, but this was the first time in my life I got to partake in it fresh off the range. The log-shaped cake was crusty on the outside, fluffy in the middle, and gooey near the center, meaning I got to enjoy this dessert three different ways. Top that off with the free cup of tea provided by the man at the tourist information center, and the entire Baumkuchen went down beyond fast. Was für ein köstliches Festmahl (What a delicious feast)!

Little Mt. Fuji

With a belly full of cake and desire to burn calories, I left the building, announcing my intention to go hiking around Ninoshima. The man who taught me how to make Baumkuchen directed me toward the trail leading to Mt. Akikofuji, the taller of Ninoshima’s two principal peaks. The route runs through a residential district, right between the locals’ houses, but the numerous signs leading the way promise tourists that they will soon be climbing, so worry not. The trail begins in earnest at a concrete ramp that transitions abruptly into a dirt path, at which point a thick layer of vegetation surrounds all who enter.

The name Akikofuji (安芸小富士) translates to “Little Fuji of Aki,” with “Aki” being a historic moniker for western Hiroshima Prefecture, and “kofuji” signifying this miniature mound’s resemblance to the iconic Mt. Fuji straddling Shizuoka and Yamanashi Prefectures. That said, though this hill (it’s not high enough to be considered a mountain by any standards) is only 278.1 meters high, the climb still proved to be a challenge with its steep incline and slippery soil. There are multiple paths that can be taken up Akikofuji (and some that ought not be taken), most of which are marked (albeit only in Japanese), but those who wish to reach the top should follow the signs marked 小富士山頂 (こふじさんちょう – Kofuji Summit). On the way to the summit, the terrain changes and the slope gets even more slippery, so I advise climbing with hands and feet for those without good balance.

Those who reach the summit will be greeted by a red, fenced-off tower, and glorious views on either side. On the east (right-hand) side is a vista of the Seto Inland Sea dotted with tiny islets and oyster rafts (pictured up top), while on the west (left-hand) side, one can catch a glimpse of Miyajima and its famous peak, Misen, through the trees. This spot was an excellent location for me to catch my breath before heading back down via a different path. The signs on the trail pointing in other directions seemed to offer other interesting spots on the island.

Recess in Nature

While the summit is obviously the highest point and sure to offer wondrous views, there is a separate observation deck further down the hill on another path. To get there, be sure to follow the signs that say, 展望台 (てんぼうだい – Observation Deck). If you make a wrong turn (like I did), you may end up at what seems to be a dead end, with nowhere to go but a single down so steep you may not be able to climb back up. If you went the right way, you’ll eventually come across a set of stairs leading up to a platform with a gazebo, which is perfect for taking a lunch break if you brought lunch with you.

Up here is also a long, blue slide that leads to a lower section of the observation deck, where one will find a short zipline for the kids. I couldn’t slide smoothly with my pants and came to a complete halt, so I climbed back up the slide and descended the stairs to the lower section like a normal person. However, I did make up for it by unleashing my inner Tarzan on the zipline after all the nearby kids had their fill and disappeared.

From here, I climbed all the way back to sea level, where I found the enormous Ninoshima Rinkai Children’s Nature Reserve. This is a wide-open park for kids to engage in all sorts of outdoor activities, and comes equipped with a large, wooden jungle gym, a ground for playing soccer, tennis courts, and a pool that draws its water from the Seto Inland Sea, to name a few. While walking around, I also came upon a sign telling the same story of Karl Juchheim that I heard while making my Baumkuchen. According to this sign though, in addition to Baumkuchen, German prisoners of war were also responsible for introducing soccer to the locals on Ninoshima, and a match between the Germans and Japanese students was recorded as the first international soccer match on Japan in history. With so many remarkable events that happened on Ninoshima, quite frankly, I’m surprised this place isn’t more popular with tourists, domestic or international.

Other Sights to See

The fun on Ninoshima continues with half of the island that I have yet to see, as by the time I was done with the Children’s Nature Reserve, it was high time for me to head home. For those craving more history, there’s a cenotaph dedicated to victims of the atomic blast, just like the ones in downtown Hiroshima. South of that is a small history museum that tells its story through art. If climbing Akikofuji wasn’t enough for you, on the south side of Ninoshima is a shorter hill called Mt. Shimotaka, and both hills combined should prove to be a great workout.

Along the way, you’re sure to take in your fair share of seascapes that you can enjoy at a leisurely pace no matter where on the island you are. Back near the tourist information center, visitors can try their hand at fishing, go on a kayaking tour, or relax at a campsite further south. There truly is a plethora or things to be enjoyed on this island, limited only by the visitor’s imagination, so to say that Ninoshima has “nothing” is an absolute lie. Ninoshima is technically within the city limits of Hiroshima despite being situated a fair distance from the city, so I recommend it as a destination for those who want a drastic change of scenery but don’t want to take a trip out of town. If you love the outdoors and loathe crowded locales, come to Ninoshima to hike, cycle, fish, kayak, learn, play, or relax by the sea and enjoy doing “pretty much nothing.”