100 Stories

Shimada Fisheries: The Bay Is My Oyster

Japan is a fascinating land that offers countless unforgettable sights and life-changing experiences, and they even rotate by the season. The most recognizable landmarks are undoubtedly Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines, given how often they are portrayed in media overseas and the fact that a lot of them have been registered as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Be that as it may, tourists the world over don’t come to Japan just to see old architecture, and after a hand-washing here, a bell-ringing there, and some fortunes or talismans to take home, it’s a cold, hard fact that temple burnout will eventually creep up. If you’ve got temple burnout by the time you’re in Hiroshima, rest easy knowing that we’ve got no shortage of fun places and experiences that have nothing to do with religion. One option is gourmet tourism, and unbeknownst to many visitors, one of Hiroshima’s yummy treasures lies in wait in a location you might not expect: the bottom of the sea!

- Areas

- Category

Hiroshima Prefecture is famous for a wide variety of foods, most notably okonomiyaki and oysters. Shimada Fisheries is one of many companies that harvests oysters from Hiroshima Bay in Hatsukaichi City, right across from Miyajima. They offer a tour that lets sightseers catch a glimpse of the oyster harvesting process live as fishermen retrieve their morning haul. There are a couple caveats to be aware of before joining, however: it starts at 7:00 a.m., and phone reservations are necessary and must be made in Japanese. The latter should be no obstacle, as those who don’t speak Japanese can have a representative reserve on their behalf, so I’ll delve more into the former.

The boat for the tour departs at 07:00, but participants are asked to arrive by 06:50 to hear some explanations and prepare. At this time in the morning there are few modes of public transportation available, but at least the streetcar and JR lines are up and running. If you’re staying around Hiroshima Station, there’s a train that departs at 05:50-something that’ll take you to Miyajimaguchi Station with plenty of time to spare. On the other hand, if you’re like me and based downtown, your best recourse is to take the slower streetcar, which requires a transfer at Nishi-Hiroshima Station. Normally, the #2 runs straight from Hiroshima Station to Miyamjimaguchi, but at this time of day the #2 starts at Nishi-Hiroshima. In order to make it on time for the oyster boat tour, you should be waiting at the Hondori streetcar stop no later than 05:40 to catch the #3 bound for Nishi-Hiroshima, and make sure you’re on the west platform where the streetcar travels northbound. The transfer at Nishi-Hiroshima Station is pretty streamlined, but be sure to tell the conductor before you get off that you’re transferring to get a transfer ticket. You’ll pay the fare for this leg first, and with the transfer ticket you’ll pay the difference once you reach Miyajimaguchi.

Watching Fishermen at Work

Once the streetcar hit Miyajimaguchi, I left the station and immediately turned right, from which it’s about a twelve-minute walk to Shimada Fisheries. If arriving from JR Miyajimaguchi Station, first walk up until you see a brown bus stop across the street, and then go right. Keep to the sidewalk on the left, but as the sidewalk is inconsistent you might find yourself on the street at times, so watch out for cars. The clock was fast approaching 06:50 when I was partway there, so I picked up the pace and made it right down to the wire, with the boatman already waiting for me in front of the building. I told him about my reservation and he immediately took me to our vessel for the day. Visitors are advised to dress warm for the early morn because the motorboat doesn’t have a cabin or heaters, and that sea breeze can really bite into you. I counted myself lucky that the boat even had a canopy; he probably went with that one because rain was in the forecast.

We took off right after I boarded, and I was the only participant in the tour today. I intentionally picked a weekday morning in early March for warmer weather and to avoid potential crowds that may arise from spring school holidays. The boatman doesn’t talk much between departure from the pier and arrival at the oyster reef, but told me that if I had any questions, I could ask them whenever. This could be a potential hurdle for foreign tourists as the boatman seems to only speak Japanese, and according to him they get plenty of foreign tour groups, mostly from other Asian countries. I think there’s room for improvement on this leg of the ride in that the boatman could use this time to break the ice and start the tour with gusto. Alas, it was up to me to show initiative and start the conversation to make the ride more informative and enjoyable.

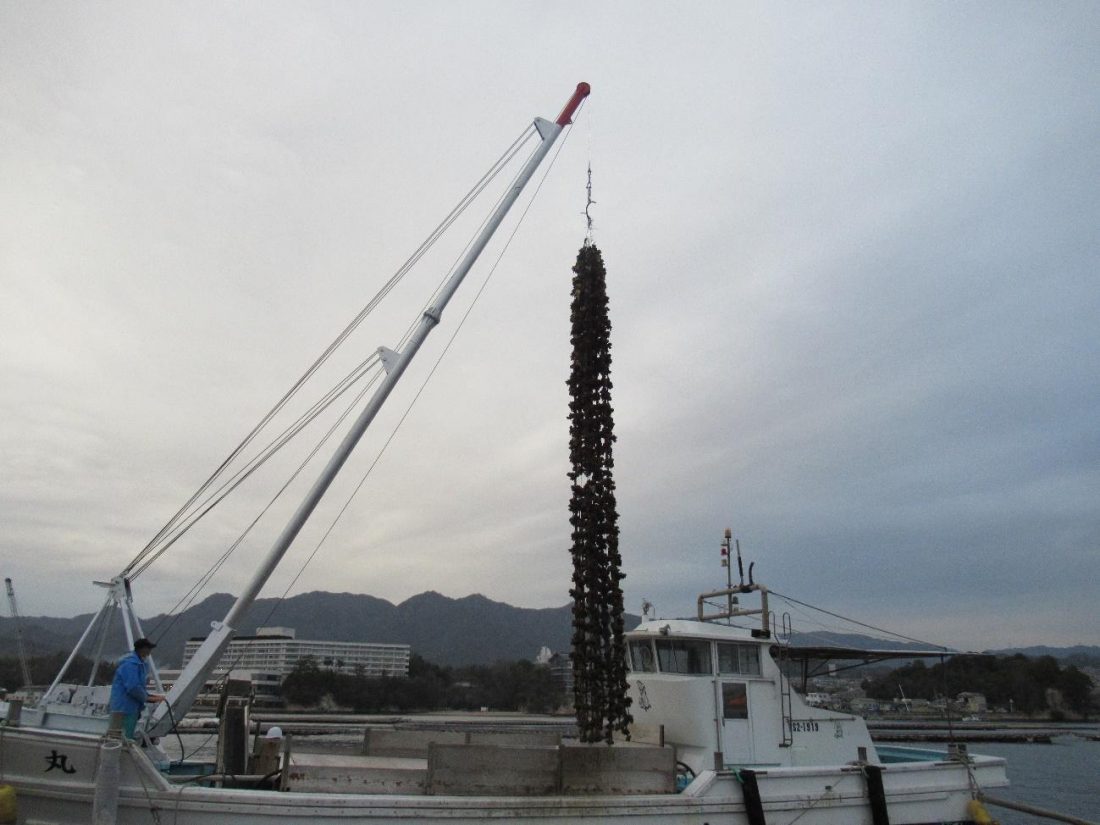

Oyster season hits its peak in the winter, but Shimada Fisheries offers this tour between November and May while the weather is cool and the oysters thrive. In Hiroshima Bay, oysters are cultivated under rafts like these where they hang from lines underwater. When left like this, oyster progeny spawn on top of their predecessors on the line, creating a chain up to ten meters long! A fisherman first attaches a hook to a batch of submerged oysters before a crane on the boat pulls them to the surface. Fortunately, the boatman provided ample information during this segment of the tour.

“At this point, they’re about halfway done,” he explains as the crane continues to pull.

“There’s still more, huh?” I reply in astonishment.

“That’s right, the other half is coming up,” he elaborates.

“They look really heavy,” I comment.

“They are. You’ve seen them before, but things like the color and shape are completely different.”

“I know, right?”

As you can see, what was just pulled up from the depths of the sea don’t exactly resemble what we’re accustomed to seeing at restaurants. Those oysters are still in their razor-sharp shells, covered in dirt and attached to one another like an inseparable, marine family tree. From the deck of the boat, a worker uses a heavy-duty cutter to snip these oyster lines, and the crane lowers to payload bit by bit until the lines are completely cut and all the oysters are lying on the deck.

This one boat will haul oysters four times this morning, so the fishermen waste no time in repeating the pulling and cutting. As I was only watching the production of one company’s boat on this one oyster reef, I paused to fathom how many oysters could be harvested from Hiroshima Bay in a single morning with all these vessels combined. After the second go-around, the boatman took me to our second destination.

Prayer by Sea

We left the oyster reef and headed in the direction of Itsukushima Shrine’s floating torii, a symbol of Miyajima itself. It was akin to taking the JR or Matsudai ferry from Miyajimaguchi Port to the island, but much better because I was taken straight to the floating shrine itself and had a private viewing spot no less! At the time, the torii was covered by scaffolding, which may or may not have impacted how close we could get, but regardless, here is about where our boat stopped today.

The first thing the boatman told me as soon as we stopped was to look down. The waters of Hiroshima Bay were crystal clear and I could see the sediment and shells at the bottom! My guide then clarified that this has been a sacred site for centuries whose location was selected for its accessibility by boats. Naval ships on their way to war would stop by to pray for victory, and simple fishing dinghies could also pay a visit and bid the sea goddess watch over them in the rough seas and bless them with a bountiful catch. While I stood in front of the partially concealed torii admiring what little I could actually see, I noticed that the wind was cooler on this side of the bay. Apparently, that’s because we were in the middle of the water and the island of Miyajima has fewer buildings to block the nippy breeze.

Regrettably, the torii remains under renovation, and even under the scaffolding it’s easy to see that its color has faded, which justifies the renovation works. The project started in the summer of 2019 and the original plan was to have it done in time for the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, but at this rate it looks like they won’t make that deadline and renovations may last until the end of 2022. If I were to pray for anything at this point, it would be for Itsukushima Shrine to be fully renovated as soon and safely as possible.

Back for Breakfast

From here we slowly sailed back to the pier at Shimada Fisheries, which was the longest and most serene leg of the journey. I had my first breakfast super-early this morning and I could feel my appetite returning, so for the rest of the tour I was engrossed in my thoughts of second breakfast (an optional addition to the tour), which was certain to include oysters. To stave off hunger and boredom, I once again struck up some idle conversation with the boatman.

“Hey, I just thought of something. Does the sea smell like fish, or do fish smell like the sea?” I piped up.

He seemed rather perplexed with his reaction. “I’m sorry, what?”

I rephrased my question. “What’s this smell? It smells like fresh fish.”

“That’s the smell of saltwater,” he answered.

“Oh, right, and it’s because the fish live in there that they smell like that, right?”

“Yes, that’s right.”

When we touched down on dry land once again, the boatman showed me a haul brought back by another fishing vessel. The oysters piled up on deck could absolutely feed dozens of families, and after being cleaned, shucked, and shipped off to restaurants and stores, they will. My guide then picked up a clump of three oysters stuck together, explaining that this was actually three generations of oysters bound underwater. It was comparable to a grandfather, father, and son, and a perfect parallel to how generations of humans living in Hiroshima have been able to enjoy this regional delicacy for centuries.

I got my fill of photos of the oyster transportation process and was soon taken up a staircase to a terrace where I would partake in an oyster fisherman’s breakfast. I was provided with a charcoal grill, a bowl of four oysters to be cooked, a pair of tongs, a heat-resistant glove, a tray for eating the grilled oysters, and a pair of chopsticks. The boatman said he’d be back with some oyster rice soup and left me to my grilling. This was actually my first time grilling oysters on my own, so I was grateful for the instructions provided in Japanese, English, and Traditional Chinese. Since I am able to read all three, I can confirm that the translations were accurate and detailed enough for me to grill worry-free, but of course the original Japanese was more comprehensive by a long shot. The warning at the bottom telling customers not to eat raw or half-cooked oysters and waiving the establishment of responsibility is only in Japanese, which I find inexcusable as it’s obviously the most important clause to translate and could save a foreigner’s life.

Moment of Joy: Just Me and the Sea

Right as my first two oysters on the grill were done, the boatman returned with the oyster rice soup and my breakfast spread was complete. It was packed with rice and topped with colorful veggies, and much to my delight I found six oysters underneath when I swirled the soup around with my ladle. Being the only participant on the tour, I also had the entire terrace to myself, commanding a spectacular view of the pier with various boats docked and some pine-clad islands in the distance. I could truly enjoy breakfast up here at my own pace, warming my body with the piping hot soup and finding enrichment in learning to grill and pry open my own oysters. I don’t care if none of the oysters contain pearls; by the end of this experience, I’d already found my own treasure at Shimada Fisheries.

The Rest of the Day

It was only 8:30 a.m. when I finished my breakfast and paid for the tour and meal, and I had the rest of the day ahead of me. Before leaving, I asked a nearby woman if I could view the oyster shucking process, and she took me upstairs where I could peek into a room with some ladies furiously cracking open oysters for packing and shipping. The pace at which they worked was amazing, but I left quickly after, deciding not to disturb them with my presence for too long. When you’re done with the tour and breakfast, you can take the ferry to Miyajima to check out the sites there, take the JR train or streetcar back to Hiroshima City, or go just about anywhere else; the world is your oyster. At this point I was feeling sleep-deprived, so I chose to board the streetcar back home for a little nappy.

An oyster boat tour with Shimada Fisheries is an awesome learning experience for those curious about the origin of a famous Hiroshima delicacy. It’s not that popular with foreigners at the moment due to its lack of accessibility, but as the boatman said to me while we sailed across the bay, they wish to see more foreign tourists come visit, and word of mouth from past foreign customers can be a huge help. I for one believe in finding alternative ways to enjoy my favorite places, and with its unique approach to Itsukushima Shrine and exclusive oyster extraction show, this tour gives visitors one more reason to spend some extra time to relish the Miyajimaguchi side of the bay. To any tourists who swing by the Miyajima area, I’d offer this one pointer: the oyster farming experience with Shimada Fisheries is a pearl tucked within Hiroshima Bay that is definitely not to be overlooked!