100 Stories

Hinterland Hiroshima: Getting Lost at Taishaku Gorge

Japan has 47 prefectures, and save for a few exceptions like Hokkaido and Nagano, they tend to appear tiny on a map. Contrary to its miniscule appearance, however, Hiroshima Prefecture is actually deeper than most people would think, with a plethora of sights to see and places to explore. Granted, there is an emphasis on coastal destinations–Miyajima, Hiroshima City, Kure, Okunoshima, Onomichi, Fukuyama, etc.–because they’re more accessible to tourists and thus end up being more popular. The northern, inland reaches of the prefecture are harder to get to without driving, and as a result, Hiroshima’s hinterland sees fewer visitors than it could. However, Hiroshima’s mountainous interior offers scenery that’s so drastically different from the urbanized Setouchi coast, some tourists may even wonder if they’re still in the same prefecture. To that, I say that Hiroshima’s two-faced nature is but one pivotal aspect of its comprehensive beauty.

One natural marvel that’s often touted as a must-see in domestic travel guides is Taishaku Gorge, which runs from Shobara City to Jinseki Kogen Town, with Upper Taishaku occupying the former and Lower Taishaku encroaching into the latter. The gorge consists primarily of limestone that was continuously eroded by the waters of the relentless Taishaku River, forming imposing cliffs, incredible archways, and even an intricate cave off to the side. As stated before, the best means of transportation is a private vehicle, but by no means can it not be accessed via public transport. I live to test out these methods, so for this journey, I took a red-eye 6:20 a.m. bus from platform 9 of the Hiroshima Bus Center downtown (it’ll depart even earlier from Hiroshima Station if that’s your base). No reservations are required for this highway bus, and IC cards are accepted, so all you need to worry about is having enough on your balance (or enough ¥1,000-yen bills to charge your card) before dismounting. I rode the bus all the way to Shobara Station, from where I would catch an 8:25 a.m. transfer and alight at 帝釈B.S. (たいしゃくばすすとっぷ – Taishaku Bus Stop), a green, secure waiting booth on the side of the highway.

March to the Gorge

Before I talk about the journey to Taishaku Gorge, allow me to remind you that the bus stop is four kilometers away from the town just outside Upper Taishaku, which roughly equates to a one-hour journey on foot, one way. For that reason, I strongly suggest ducking into the waiting booth to have a seat, a snack, and/or a drink while mentally preparing for the expedition ahead. I did just that, and since the only way to go is down the stairs behind the bus stop, down I went, where I was faced with a fork in the road. My smartphone’s map application proved to be rather deceptive in this rural area, and I ended up trying several wrong ways before finally figuring out the right one. It should go without saying that if you walk down a desolate, country road, and start to hear dogs barking, odds are, you’ve stepped on to someone’s farm rather than a tourist destination. Long story short, take this eerie concrete tunnel that passes under the highway.

Upon exiting the tunnel, stop for a second and look to your right. The unkempt staircase leads to the other bus stop where you’ll catch your ride back to Hiroshima City. Before setting out towards the gorge, it may be a good idea to ascend the staircase and ascertain the return bus times (take a picture; it lasts longer) so you can better time your walk back from Taishaku Gorge. After that, walk straight ahead from the tunnel exit until the road merges with a busier freeway.

It’s actually from here that the gorge is four kilometers away, but with all the marvelous autumn foliage and rushing cars urging you to hurry up, it won’t feel like such a long march. Additionally, don’t be fooled by the sunny weather in these pictures or your online forecast. The northerly areas of Hiroshima Prefecture are considerably colder than the cities we’re acclimated to, especially this early in the morning, so pack some extra layers, a scarf, and even gloves if the cold bothers you. Under normal circumstances, I would advocate walking on the right side where you’d be facing oncoming traffic and won’t be surprised by passing vehicles, but there’s a footpath on the left side for pedestrians so that’s the obvious choice. That said though, yours truly foolishly kept to the right thinking that a right turn was coming up (according to the map), when in reality, the freeway naturally curves right to pass over the highway where the bus dropped me off. I eventually moved over to the left side when I saw a crosswalk, but by then, I was already in town.

Walking the Gorge

When I arrived in town, the pedestrian footpath was elevated above the street, so I went down some steps, crossed the vermillion bridge, and kept going straight in the direction of the gorge entrance. Sometime later, I happened upon an establishment called 弥生食堂 (やよいしょくどう – Yayoi Cafeteria), where weary trekkers can stop for lunch and adventurous explorers can rent bicycles to traverse the gorge even faster. However, they don’t provide helmets, so those who wish to ride with a helmet should bring one from home (alternatively, various stores in Hiroshima City sell helmets).

My first order of business was to enter Yayoi and inquire about the possibility of cycling all the way to Lower Taishaku from here. The man replied that there’s a point in the middle of the gorge that’s too rugged and steep to cross by bike, and that if my goal was Lower Taishaku, I would be better off foregoing the bike and walking all the way down. It’d make no sense to bike to the halfway point, turn around to return the bike at Upper Taishaku, and start the walk all over again. Apparently, there used to be a bus that shuttled visitors between both ends of the gorge, but with the recent decline in customers, that service has ceased, and now the only other way was to summon a taxi from Tojo Station northeast of here, which I wasn’t willing to do.

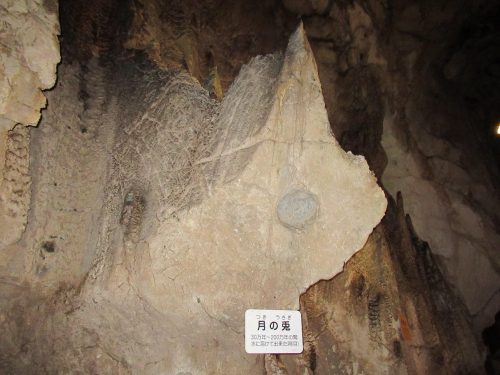

Thus, I opted to simply walk the gorge and see how far I could get. No more than three minutes had passed when I encountered Haku-un Cave. I paid an admission fee and ascended the stairs into the cavern, which is so narrow, tourists have to occasionally stop to allow opposing traffic to pass. Inside Haku-un Cave are a bevy of interesting limestone formations that took anywhere from tens of thousands to millions of years to be carved out by erosion. The shapes are ambiguous, so recognizing them as what the signs say they are requires an inkling of imagination. All signs are in Japanese, so if you can’t read the descriptions, feel free to imagine whatever you want from any of the rocks in here. The one above is supposed to be the Moon Rabbit that is either making medicine or rice cakes on the Moon, depending on whom you ask.

The cavern continues for a short while, but at the very back is a dead end, forcing visitors to go back the way they came. Local speleologists don’t know what lies beyond this grate other than an opening on the other side, which explains why wind blows through here. This cramped crevice continues for quite a while, so who knows when or if they will be able to explore all the way to the end.

I exited the cave and followed the Taishaku River due south until an older woman sitting in a chair warned me about the impending danger of rockslides in the area. When I passed the warning sign, I looked up and saw that she wasn’t kidding; the fence was already significantly warped by the weight of loose rocks that had fallen off the cliff. While I wasn’t afraid of being smashed by geological debris, the warnings did make me more alert of my surroundings and reminded me not to linger by cliff sides for too long.

Other points of interest in Upper Taishaku include the Demon’s Gate and Demon’s Monument. What is now the Demon’s Gate used to be a tributary of the Taishaku River, but a great volume of rocks fell from above and blocked up the waterway, creating what we see today. The Demon’s Monument is a vertically-standing boulder on a cliff, said to be dedicated to the demons who allegedly created the arches in this gorge, called “Onbashi” and “Mebashi.”

Moment of Joy: See You Next Fall

I swung by Taishaku Gorge during the latter half of November, when the autumn leaves were still radiant, but on their way down. As I strolled by the riverside, the wind would blow on the trees, sending leaves tumbling in a golden flurry. The phenomenon would happen in an instant, but that instant felt longer upon seeing these leaves that seemed to wave at me as they settled onto the surface of the water. It was so riveting to see that I slowed down my walking pace a great deal in order to savor these autumnal blizzards for longer, constantly awaiting the next flurry of foliage.

Overarching Onbashi

After a while, I arrived at Onbashi, the colossal arch most tourists come to see and photograph. It’s as much fun to pass under as it is to gaze at, and from here I decided to walk as close as I could to the halfway point between Upper and Lower Taishaku. Shortly after Onbashi was a staircase leading down to the riverbed where the pooling water shone a vivid aquamarine. The fallen foliage further accented the crystalline water like glitter, easily making this the most beautiful segment of the river I lay eyes on that day.

Past this point, there were groups of visitors having picnic lunches on the grassy areas by the walking path. The sight of them enjoying their midday meal in Mother Nature’s backyard was starting to make me hungry, so I decided to turn back at the next landmark. My last destination for the day was Dangyo-kei, or the Tumbling Fish Canyon, which are the strongest rapids in all of Lower or Upper Taishaku.

The Journey Continues

I couldn’t see Lower Taishaku today, but if anything, that’s justification to return by bus and hike here once more. Further south of where I stopped are even more points of interest, such as Somen Falls, Kashiwa Boulder, and Lake Shinryu, where visitors can take a relaxing boat ride on the river and get to know Taishaku Gorge on a deeper level. For now, the priority was food, which I obtained at Keisansho, a restaurant between Yayoi Cafeteria and Haku-un Cave. The shops around here (including Yayoi) tend to feature noodle dishes like soba and udon, but I decided to go for something a tad more rustic: dango jiru, which is basically soba and rice flour dumplings shaped like discs and cooked in the same broth that’s used for soba. Quantity-wise, it’s on the light side, but it ended up tasting exactly like soba, and the dango (dumplings) pack a more noticeable soba punch that would otherwise go undetected when slurping their longer, thinner equivalent.

The walk back to the bus stop was not as grueling as before as I now knew the way, and this is one instance in which the adage, “the journey is the destination” proves true. After all, if walking is what you’ll do at the gorge, why not get in a little more exercise on your way from the bus stop? For those who cannot walk that far or drive, there’s always the option of riding the bus from Hiroshima to either Shobara or Tojo and taking a taxi to either end of Taishaku Gorge. With this destination being accessible through so many avenues, there truly is no excuse to overlook the hinterland during a longer stay in the Hiroshima area. Heading up here is like visiting a different prefecture without leaving Hiroshima, because all you’re really seeing is the other half. To get to fully know Hiroshima Prefecture and its many facets, an excursion up to Taishaku Gorge is a necessity for balancing out the Setouchi seascapes, so what are you waiting for? The hinterland awaits!