Now & New

- Explore

Simose Art Museum Grand Opening: Another Reason to Visit Otake

Oh, Otake, you poor, small town sandwiched in between Miyajima and Iwakuni, always having your own appeal overshadowed by your neighbors’. Even among Japanese—no, even among Hiroshimarian tourists, Otake gets ignored in favor of Itsukushima Shrine and Kintaikyo (justifiable, but still) and most visitors getting off at Kuba or Otake Station are elderly, local hikers on their way to Mikuradake. Since there are frequent bus services between town and the mountains—more frequent than I would expect Otake to have—a day trip spent hiking here has always been a good idea, but only if you’re the outdoorsy type of tourist. In addition, the Koikoi Bus line runs through the center of town between Kuba and Otake Stations, stopping at local hospitals and shopping centers. Up until recently, the Koikoi Bus was thought of as something only locals used when running errands since most of the stores in downtown Otake can also be found in Hiroshima City, but with the opening of a new tourist attraction in Otake’s urban center, that mode of thinking is about to change.

The Simose Art Museum is a sleek, state-of-the-art exhibit hall that opened on the 1st of March this year, complete with a garden, a rooftop observatory, a gift shop, a French restaurant, and accommodation facilities. Its waterside location exploits the existing beauty of the adjacent Hiroshima Bay, and the use of land for a museum is much more appreciated than the parking lots and factory grounds that occupied the space before. As the grand opening of the Simose Art Museum was aligned with the Hina Doll Festival—which is observed on the 3rd of March as well as on the days leading up to it—the inaugural exhibition was Hina doll-themed and would last all the way into Golden Week.

Where Art Thou?

Otake may be a bit out of the way from Hiroshima City, but given the availability of buses, the Simose Art Museum doesn’t feel so inaccessible. All one has to do is take the JR Red Sanyo Line past Miyajimaguchi to Kuba Station, step outside the building, and turn right to find the Koikoi Bus, which runs periodically between Kuba and Otake Stations from the morning to late afternoon. I decided to hit up the museum a week after their grand opening as early as I could (right after the start of their hours of operation), so I got on a Koikoi Bus and alighted at the local YouMe Town, the closest bus stop to the Simose Art Museum. To fuel up before my art gallery tour, I dropped by my usual café, Silvia Coffee, which was dishing out free breakfast with any drink order.

The breakfast comes with a buttered toast triangle, a hardboiled egg, a coleslaw salad with dressing, and the option to add strawberry jam or Ogura (mashed sweet red beans) to one’s toast. All of this for the price of one drink gives quite the bang for one’s buck, and while my beverage may have been on the pricey side, those who wish to maximize cost performance can simply order the basic hot coffee for which this café is famous. After finishing my breakfast and gulping down the last of my banana juice, I hit the road leading to the Simose Art Museum. When I got to the entrance to Harumi Rinkai Park, there were signs directing visitors to the art museum; after going through the gate and walking for a bit, I came across the museum entrance, flanked by perky pink trees and manned by a friendly security guard.

From there, it was still a bit of a walk before I finally reached the museum building, purchased my ticket, and began to look at the exhibit. Admission may cost a steep ¥1,800 but it truly is a high-quality exhibit, and the ticket is valid all day, meaning visitors can leave in the middle to grab lunch or take a break elsewhere before resuming their perusal of the gallery. In the first room, there were Hina dolls in glass cases on display, along with a wall where a projector cycled through bilingual descriptions of the featured works.

Inside each glass case were informational plaques explaining the title, time of production (if known), materials used, and artist name, followed by a brief description and backstory in both Japanese and English. Some plaques may have a numeral icon indicating what number to select when using the audio guide. The audio guide can be accessed on one’s own smartphone by scanning a QR code provided throughout the museum, and explanations are available in Japanese and English.

The fun doesn’t stop with the dolls themselves, as even back then, they were making “toys for toys,” that is, tiny accessories for the dolls to use in order to enhance playtime. Inside multiple glass cases were miniature tables, containers, folding screens, instruments used for tea ceremonies, and even shrunken board games such as sugoroku (Japanese backgammon), shogi (Japanese chess), and Go (a five-in-a-row game), with dice and game pieces to boot. The dolls below are playing a game called karuta, a card game similar to slapjack wherein a player designated as the “reader” reads part of a poem and the other players slap the corresponding picture card.

Shipped Overseas

I exited the Hina doll exhibit hall and found myself in a corridor with large windows, where I could make out a spectrum of shipping containers floating in water at the edge of the sea. Each shipping container was its own room full of artworks centered on a certain theme, and there were eight in total. On top of that, these floating shipping containers can be relocated at will as exhibits change over the course of the year, and the corridors connecting them can also extend and retract, altering the route visitors take.

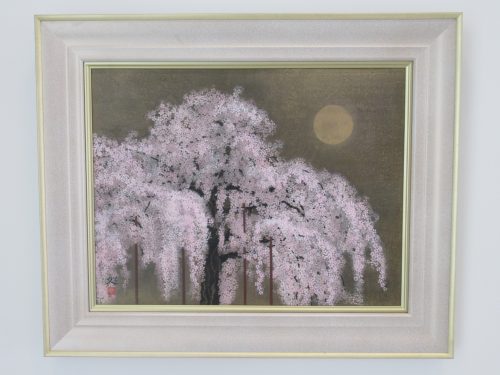

There was a plentiful mixture of Japanese and Western artists, with big names such as Matazo Kayama, Taro Okamoto, Simon Yotsuya, Marc Chagall, Émile Gallé, and the Daum brothers. Inside the first shipping container was yet another doll display, this time featuring ceramic people in kimono admiring cherry blossoms. The following rooms featured other media with sakura, most notably Western-style paintings by Japanese artists, also known as yōga (洋画), not to be confused with the Hindu philosophy and exercises. One of my favorite paintings that day would have to be this one by Matazo Kayama, featuring cherry blossoms underneath a full moon, with each petal meticulously painted to stand out from the tree.

In the fourth shipping container were pieces of Meissen porcelain that took on various forms, from dolls to full pieces of furniture. The signs didn’t mention the names of any specific artists, but rather that everything here was produced in Meissen, Germany, a city so famous for its ceramics that a style of porcelain artwork was named after it. There were lots of wacky subjects made from Meissen porcelain, such as “Chinese Children (who didn’t look the least bit Chinese to me)” and “Monkey Orchestra,” wherein every single monkey was given a unique outfit and musical role to play in the symphony. However, the most impressive ceramic piece in the room would without a doubt be this table, which not only features a life-like painting on the face, but also has a colorful leg decorated with porcelain flowers that seem to creep up the table.

Other shipping containers featured nature in all four seasons, represented through an abundance of media like traditional Japanese-style paintings, Western-style paintings, and ornate glass work. I was particularly fond of the glass vases pictured below, depicting snow-covered trees in winter, with the sky being unusual hues of orange or green. Masterpieces such as these were dominated by French Art Nouveau glass artists Gallé and Daum.

The sixth shipping container was probably one of the funnier ones, and while the works in here were still aesthetically pleasing, I was more amused than moved by the abstract chairs in the room. These chairs were designed by Taro Okamoto, who was also responsible for creating the Face of the Sun at the Osaka Expo ’70 Park. In the foreground was a red stool resembling a sad apple that doesn’t wish to be sat on; visitors aren’t supposed to sit on these chairs in the first place, so they’re meant to be works of art first and actual chairs second. Following this room were two others featuring glass lamps by Gallé and Daum as well as more dolls, and before I knew it, I was back in the hallway where I started.

Down to Earth

The last part of the museum to check out was the Émile Gallé Garden, which was recommended to be seen after going through both exhibit halls. I stepped through a door leading out to a tranquil patch of greenery right by the shipping containers that commanded a clear view of Hiroshima Bay. This garden provided a much-needed bit of respite from moving through one gallery after another, and what’s better, there was a bench for me to take a proper rest and savor the nature around me. There was signage in the garden explaining some of the plants that can be seen at select times of year, and while I was seating and fiddling with the audio guide, I realized there was an entry for the Émile Gallé Garden as well (albeit only in Japanese), so I gave it a listen as I stood up to check out my surroundings.

Moment of Joy: Yard of Solitude

There was barely anyone else in the garden at any given time, and for a brief while, it truly was just me, myself, and I. As I slowly strolled along the path, crossing over water and passing by the last remaining plum blossoms, the audio guide informed me of the main plant life to be found here in spring, summer, fall, and winter. No other interruptions were present save for the cawing crows and gentle wind, and I even caught sight of the occasional bird roosting in and taking off from the trees. Simply put, the Émile Gallé Garden felt less like a tourist attraction and more like the sensation of chilling in one’s own backyard, which soothes the soul in the middle of a day trip.

Above All Else

When I was finished relishing the garden, I found one more door inside the museum leading out to the slope pictured above. At the top of the slope was an array of solar panels, but at the edge of the rooftop, I could gaze out over the shipping containers at nearby islands in the Seto Inland Sea. What was once a vista reserved exclusively for workers in these seaside factories in Otake has now become accessible to the public thanks to the Simose Art Museum. If there is any one work of art to look at before going home, it would be this view, as this plot of land occupied by the museum is indeed a masterpiece in its own right.

The Simose Art Museum alone has the potential to drastically increase the number of tourists to Otake in the future. I myself already intend to return another day when the exhibit changes, or perhaps even to eat at the French restaurant if my budget ever allows. Since the restaurant is a separate building as also by the sea, I’m bound to have a different but equally amazing view while eating, and I cannot even fathom how stunning the seascape must be when the setting sun tints everything a mesmerizing orange.

Spring—which commonly represents the start of a new year in Japan—was the perfect timing for the Simose Art Museum to open, and bodes well for the city of Otake. If subsequent exhibits here continue to amaze like they amazed me, I can see tourists from Japan and abroad attempting to work Otake into their itineraries, perhaps as a site to drop by or even spend the night while visiting Miyajima and Iwakuni. As the number of visitors will undoubtedly increase as the Simose Art Museum gathers fame, a trip to Otake is advised sooner rather than later, while Otake remains a culturally and naturally rich, small town.

Written by the Joy in Hiroshima Team