Now & New

- Explore

Tenryo Joge: Hiroshima’s Connection to the Emperor

Japan has a bounty of public holidays scattered unevenly throughout the year, with some months having quite a handful of them and other months having none (looking at you, June). Depending on the reason for the public holiday, the date can be fixed, be on the nth Monday of the month, or fluctuate according to Mother Nature (for Autumnal and Vernal Equinox Day in September and March, respectively). One notable exception to the above, however, is the Emperor’s Birthday, which is normally a fixed date, but said date changes when a new monarch ascends to the Chrysanthemum Throne. During the Heisei Era (January 1989 to April 2019), this public holiday fell on the 23rd of December, which meant it was usually overshadowed by Christmas and winter school holidays, so hardly anyone noticed His Majesty’s big day. With the turn of the Reiwa Era (May 2019 to the present day), the Emperor’s Birthday has been celebrated on the 23rd of February since 2020, and thus, more of us pay attention to the date as the bulk of us abruptly have the day off work or school.

For most of Japan’s history, the imperial capital was in Kyoto, Nara, Osaka, or Tokyo, so where does Hiroshima fit into the equation? The answer lies in Joge, a tiny, rural district in present-day Fuchu City that was once designated as a “tenryo (天領),” meaning land that was under direct control of His Majesty, as opposed to belonging to the lord of the local domain. Long ago, when the Iwami Ginzan silver mine in present-day Shimane Prefecture produced approximately one-third of the world’s silver, that precious metal had to be transported on land via the “Silver Highway” to Kyoto, and the town of Joge just so happened to be one of the stops on said highway. However, in 1698, the Mizuno clan—which ruled over the Fukuyama Domain—collapsed, so this part of Bingo Province (nowadays eastern Hiroshima Prefecture) fell under direct oversight of the shogun. The Iwami Ginzan established a branch office in Joge that generated a vast amount of wealth from the late Edo through the Meiji Restoration; the silver from this branch office ended up funding both the shogunate and the then-new imperial regime.

Information Center? Gift Shop? Local Diner?

To see all this shogunal and imperial history with my own eyes, I made my way to platform 6 of the Hiroshima Bus Center and took a two-hour ride to Joge Station, and what better day to do so than on His Majesty’s Birthday? I alighted the bus in front of the station, but what was more noticeable than the ticket gates or train tracks was the business inside the station building itself, “Manmaruya (まんまる屋).” On the front door were some plum blossom decorations and posters advertising ongoing events around town, including a special exhibit inside Manmaruya itself. The Hina Doll Festival, alternatively known as Girls’ Day, falls on the 3rd of March every year, but the Hina doll displays are rolled out in Joge on the 23rd of February (no doubt to coincide with The Emperor’s Birthday), which meant I would be one of the first to view them.

In the back of Manmaruya was a Hina doll display featuring Gunpla models, which debuted in years past but was brought back by popular demand. There were small stands with information on specific Gundam models on the tatami mats, and on the wall above the display was a pink banner congratulating a certain “Takushi Tanaka” on getting married. This certainly was a lovely and out-of-the-box way to notify everyone in town of one’s wedding, and I myself just might aspire to something this geeky when my big day comes. Besides the Hina doll display, Manmaruya also has shelves of cute statuettes and local souvenir foods such as salted veggie chips, konnyaku jerky, and kuruma-fu, or wheel-shaped wheat gluten.

If you look past the shelf in the picture, you’ll see a white wall with a diagram indicating train stations along the JR Fukuen Line, as well as a green striped awning where customers order and pick up food. Manmaruya also functions as a small eatery with tables and chairs for diners to enjoy their meals indoors, but what’s interesting is that the menu du jour changes depending on the day of the week. Manmaruya is a café on Mondays and Tuesdays, serves up okonomiyaki, yakisoba, yakitori, and beer from Wednesday to Friday, and sells boxed lunches packed with fresh wildflowers picked straight from the surrounding mountains. Usually, a national holiday means Sunday business hours and schedules, but as The Emperor’s Birthday was on a Thursday this year, they were grilling all the things today. There’s a variety of okonomiyaki around these parts call “Fuchu-yaki,” which substitutes ground meat for pork slices, but they don’t sell that here. I was advised to find a restaurant around the Fuchu city center, but I know for a fact that restaurants serving Fuchu-yaki can be found around Hiroshima City as well.

White Wall Street Sights

After checking out Manmaruya, I swiftly made my way to the old town and its main street, awash with white-walled houses reminiscent of yesteryear. I decided to walk the entire length of the street from west to east and take photos the entire way, which made my first destination the Industry and Commerce Event Hall, a charming blue building that is free to enter. The first room one notices when entering is the large exhibit room on the first floor, which had a bunch of tables on one side, each occupied by a multitude of Hina dolls. To the left of that display was a monitor which provided information not only on the Hina Doll Festival in Joge, but also on the myriad tourist sites and activities in Joge in general. What’s more, all this information is available in Japanese and English, so I played with the touch screen monitor for a while to learn more about the history of Joge and stuff to do around town.

Elsewhere in the house were models of the Old Tanabe House—the residence of a famous money lender that was also used as a sake brewery back then—and of the famed sports stadia in Hiroshima City, such as the Mazda Zoom-Zoom Stadium for the Hiroshima Carp baseball team. On the second floor, visitors are invited to open the blinds and window to gaze out at Mt. Okina in the distance, standing imposingly at 572 meters. As I also had an advantageous view of the white-walled street below, it was worth entering this building for this one photo opportunity alone.

Just a little west of the Industry and Commerce Event Hall lies the Inagaki Photo Studio, where locals go to have professional photos of themselves taken. Naturally, the store interior was filled with Hina doll displays and was every bit as photogenic as one would expect, but nowhere near as precious as these two dolled up girls posing for a photoshoot in front of the store. They were extremely peppy, and I think one even greeted me with “konnichiwa;” the Fuchu locals are so friendly and polite it probably rubs off on the children!

I finally started walking down the street towards the tourist information center, where I found the Christian church right across the street. The building is only open on Sundays when services are held, but that didn’t stop me from photographing its old-fashioned exterior. Since the church was rather tall and I only had so much space to back away for a picture, I had to snap this one lying on the street when no cars where driving by.

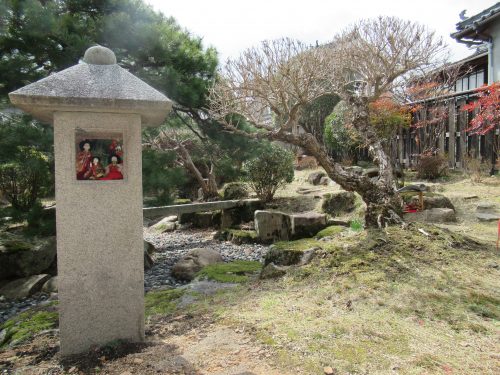

One nearby facility that was open was the Kadokura Residence Garden, which could be accessed via an open gate right behind the church. Not too many flowers were blooming in mid-February, but there were Hina dolls hidden throughout the garden, which justified walking multiple rounds through it. It was a fairly small garden, but there are multiple paths one can take, and crossing the stone bridge over the river of rocks while avoiding the pine needles was a fun challenge for me.

Gallery Hopping

My next destination was the Joge History and Culture Museum, situated inside the house where Michiyo Okada was born. Okada was the basis for the character in Katai Tayama’s “The Futon,” and the second floor of the museum is dedicated to Okada’s life story. However, what I was more interested in was on the first floor outside the main exhibit. In the front room there were tables of Hina doll displays and other spring-related artworks made by local elementary school kids, each of which was cute in its own way.

Elsewhere around the first floor were Hina Festival-related crafts made by even younger children, even babies less than a year old. In the back was a display of antique Hina dolls, some dating back to the Edo period. There were rooms in the regular exhibit showing off items more typical to Joge’s history, but photography of those sections was forbidden.

By the time I was finished, my stomach was screaming for food, so I stopped by Joge Garo for a snack break. Joge Garo is another art gallery that also has a café space, so that’s where I went first. The café sells a simple curry lunch, but since I wasn’t feeling like curry at the time, I went for a wagashi and hot cocoa set. I was given two choices for my snack, both of which were local to the area, but I went with the “hyotan monaka,” a gourd-shaped wafer sandwich with azuki bean paste on the inside. It wasn’t much, but it staved off hunger for a bit, so I paid and wandered into the gallery space to see the Hina doll lineup.

If any Hina doll display in town could beat out the Gundam-themed ensemble at Manmaruya, it would be this one. In preparation for the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris, Mrs. Shigemori, the owner of Joge Garo, arranged a magnificent scene of Hina dolls playing sports and cheering on the athletes from the bleachers. There was also another table with the Seine River and Eiffel Tower, as well as your standard antique Hina dolls, some of which also date back to the Edo period. In separate rooms were other exhibits featuring dolls modeled after Marilyn Monroe, as well as miscellaneous antiques such as pottery, clothing, and tapestries. The one old item I wanted to see the most—and the reason I dropped by Joge Garo in the first place—was not on display, and I would have to find Mrs. Shigemori herself to ask about it.

Moment of Joy: Valuable History

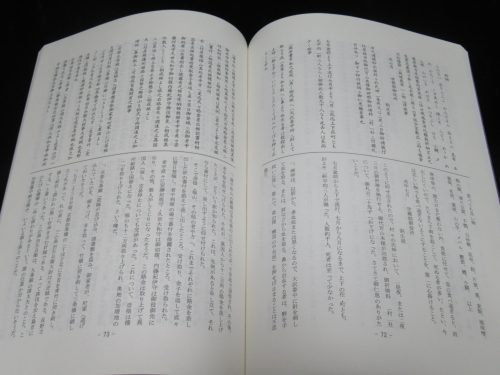

There once was a man named Shigemori Rokuemon—the ancestor of Joge Garo’s current owner—who worked for the Joge governmental branch office and left behind some documents which were compiled into the “Eitairoku (永代録),” permanent records that told of events happening in Joge as well as other domains like Fukuyama and Kyoto between 1862 and 1865. When I asked Mrs. Shigemori about the Eitairoku, she took me into a back room and showed me a replica, which could also be purchased at the gift shop inside the Joge History and Culture Museum, and allowed me to sit down and glean its contents. Almost as though fate had ordained it, in walked a Fuchu city councilman, and when Mrs. Shigemori informed him of how passionate I was to learn about Joge’s history, the elderly public servant offered to pay for that copy of the book so I could take it home with me and read it on my own time. Not only was I thankful for that act of generosity, but out of all the historic artifacts one could take home from a trip to an old town, literally taking home the story of the town itself was probably the best souvenir I could have asked for, and brought me unmatched joy for the rest of the day.

In the Taisho Limelight!

After all that magnificent art and history, I made my way for my final tourist site and the one most come to Joge to see: the Okinaza playhouse. I paid the admission fee at the entrance, took off my shoes, and stepped onto the immaculate wooden surface of the theater where folks once watched theater as early as 1925. On the walls were old photographs of the place or famous theater stars, and on either side of the hall where spectators used to sit, costumes worn on stage at the time were on display. Halfway through freely perusing the venue, one employee approached me and offered to give me a tour of the Okinaza. After saying yes, the first thing we did was cross over the wooden ramp—the path performers took to exit the scene—onto the stage to have a look at the floor.

The wooden planks were all hand-cut and fit together so that a circle in the center of the stage could be manually rotated during the performance. In addition, the screens could also be moved manually and the theater had to have sufficient ventilation as it was common for members of the audience of the time to smoke during the show. The employee then took me backstage and revealed an underground trapdoor, entirely dug by hand, from where actors entered and took the stage. I was astounded by how much thought went into just one theater in a small town like Joge, but I left feeling a lot more educated than I had anticipated.

The former imperial-owned town of Joge certainly possesses more history than one would expect a town of its size and location to have, and it was thanks to the current Emperor that I even discovered that. Furthermore, Joge has some of the nicest local charm and friendliest residents of any municipality in Hiroshima Prefecture I have ever visited. Honest to goodness, prior to this day, I had never received so many “konnichiwas” that were not initiated by myself or said by a store employee, so locals of other cities and towns in Hiroshima Prefecture should seriously be taking notes from Joge folk. Given all its quaint history, beauty, and accessibility via public transport, I truly am baffled that Joge doesn’t show up on the radars of tourists, even those who live in this prefecture. I strongly urge anyone with an inkling of interest in Japanese history or countryside scenery to walk up and down the white-walled streets of Joge and take in the prosperous vibes of this once imperial land.

Written by the Joy in Hiroshima Team