Now & New

- Explore

The Tides of Bingo, Part Two: Tomonoura Falls Toward Ebbing Nostalgia

Previously, on The Tides of Bingo, I scouted out two of Onomichi’s newest tourist sites that fully exploit the city’s majestic seascape. However, those facilities only enhanced viewing of the sea from above, having no relevance to the port or enjoying the sea itself. Thus, I took it upon myself to spend the final day of the July long weekend—which happened to be Marine Day—in a different town where I would learn about landmarks by, on, and even under the water. To that end, I set a course for neighboring Fukuyama, where I would stop for the night before exploring the port of Tomonoura.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting travel bans have not been kind to any tourist site in the world, and small towns have been hit the hardest economically. Even as domestic travel in Japan becomes safer and more commonplace (no doubt due to summer school holidays), tourists often opt for bigger cities, with Tokyo, Osaka, and Fukuoka being some of the most popular destinations. Residents of Hiroshima Prefecture may settle for an excursion to the heart of Hiroshima City if they don’t already live there, but even our prefectural capital isn’t satisfactory for some, so they go to other prefectures, leaving intraprefectural travel on the wane. To counterbalance this ebb of tourism, it has fallen on local governments to resuscitate their economies by enticing tourists to come, stay the night, and spend lots of money in their towns, with the main target being residents of the same prefecture.

Local Stimuli

In light of the easing of restrictions put on by the Japanese government months before, Hiroshima Prefecture has reinstated its “Yappa Hiroshima Ja Wari (やっぱ広島じゃ割)” campaign, which provides major discounts on participating businesses for prefectural residents traveling anywhere within Hiroshima Prefecture. The discounts mostly apply to hotels, but those who book a tour with a travel agency can still be eligible. Since I tend to travel independently, I can only speak for the hotel discounts, but in a nutshell, the prefectural government subsidizes fifty percent of the cost of accommodation, and furthermore provides vouchers to be used at participating stores and restaurants, valid for the day of and after the hotel stay. The vouchers are valued at ¥1,000 each, and the total amount granted is equal to half the cost of the hotel stay (after the half-off discount), rounded to the nearest ¥1,000. When shopping or dining, tourists need only look for the dark red poster on the storefront window that states that the establishment accepts “Yappa Hiroshima Ja Wari” vouchers, and if visitors do the math right, they can essentially eat or get their souvenirs for free.

There are conditions to exploiting this campaign, however, but hotel websites that offer exclusive “Yappa Hiroshima Ja Wari” plans will clearly state them (in Japanese). First of all, as stated before, the visitor must live in Hiroshima Prefecture, and bring some form of identification with an address that can prove so. Second of all, those under the age of 65 need to have had their second dose of any COVID-19 vaccine (it’s either Pfizer or Moderna around these parts), and those aged 65 and over need to have had their third dose. Lastly, it is necessary to bring a hard copy of proof of vaccination to the hotel when checking in or else the government-back discount will not apply. “Yappa Hiroshima Ja Wari” stacks on top of other local subsidies and kicks in after those discounts; Fukuyama City was running a tourism revitalization campaign that knocked ¥3,000 off the bill for anyone from the Chugoku (Tottori, Shimane, Okayama, Hiroshima, and Yamaguchi Prefectures) or Shikoku (Tokushima, Kagawa, Ehime, and Kochi Prefectures) regions, so I saved big bucks while helping to pump some of my money into Fukuyama’s economy.

Moment of Joy: Stacking Rewards

I knew how much I would be saving as I was planning this two-day excursion days in advance, so I took the liberty of including breakfast with my stay. A stay always costs more when meals are included, but in this case, a bigger price meant a bigger discount, and having more money knocked off was basically a free breakfast.

My particular hotel near Fukuyama Station offered the above ensemble as one of its options: I got pancakes (with free refills to boot), maple syrup, butter, hash browns, bacon strips, sausage links, mustard, yogurt with granola, a salad, orange slices, corn potage soup, chicken marinated in tomato sauce, and access to a drink bar. Needless to say, this one meal filled me up for the rest of the day, so instead of using my vouchers for lunch or snacks in Tomonoura, I nabbed some gifts to share with my family back home.

Waterside Fukuyama

Although Tomonoura is within the city limits of Fukuyama, considering the sheer distance from the city center as well as the drastic change in scenery, it truly feels like a separate town in its own right. The bus from Fukuyama Station took about fifty minutes to take me there, and dropped me off in front of the Tourist Information Center, which also functions as a gift shop, delicatessen, and miniature bus hub connecting to other parts of Fukuyama. I planned to save the shopping for last, but I was anxious to see what kinds of souvenirs were sold, so in I went to investigate.

Inside the store was a wide selection of food, drinks, and other souvenirs from all over Hiroshima Prefecture. Obviously, this included lemon-flavored products, such as bottles of cider or sauces, but this shop seemed to place the greatest emphasis on packaged seafood. Since Tomonoura is right by the sea, it’s only right that most of their specialties would be fishy, hence all the packages of surimi (擂り身 – grated fish) products like jako-ten (じゃこ天 – tiny fish ground into a patty, breaded, and deep-fried) and chikuwa (竹輪 – fish paste molded onto a stick and grilled to make a hollow cylinder). The store even sold insulating bags for customers who wanted to buy a lot of seafood and keep chilled all day until they got home. I, on the other hand, simply waited until I was ready to go home to purchase my small chikuwa, fresh and still on the stick. In modern times, chikuwa may be cooked and served on a cardboard tube to reduce costs (much to the delight of Miyajima’s deer), but this one product stayed true to the name (“chikuwa” means “bamboo ring”) by grilling the ring of fish on an actual bamboo stick.

Anyhow, I didn’t claim my free souvenirs right away, and instead headed south, with the sea wall to my left. Somewhere along that path I noticed a ship coming in to dock, so I ran through a parking lot and scurried up some stairs to the top of a sea wall to photograph it. This vessel here is called the “Heisei Irohamaru,” a modern replica of a historical steamboat that the legendary Ryoma Sakamoto himself was riding when it abruptly sank, but more on that story later.

The Heisei Irohamaru sails between Tomonoura Port and nearby Sensuijima several times a day, and I was tempted to take a ride myself until I realized I didn’t have enough time in my afternoon to properly explore Sensuijima. I decided to leave that trip for another day and simply watch the boat go, emitting smoke just like its late-Edo counterpart. To get a better angle, I moved to a different part of the sea wall, and although stairs aren’t located everywhere, the wall wasn’t too much of a challenge to climb.

East of the Sun

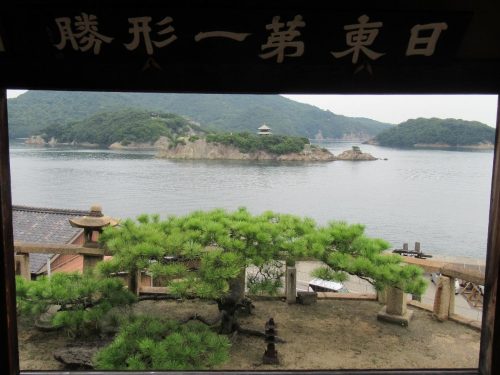

After the ship became a blip on the horizon, I jumped back down to street level and progressed up an incline and some steps to Fukuzenji, the next item on my agenda. At the entrance to the Taichoro Hall, a couple guardian statues stood before me, as did a dragon on the rim of a dried-up fountain. I went up the stone stairs and removed my footwear before stepping onto the wooden surface, then entered the hall. The main attraction here was the view out the window looking out towards Bentenjima and Sensuijima across the sea. In 1711, a Korean delegate to Tomonoura named Yi Bang-eon famously dubbed this specific landscape “The Best View East of the Sun,” in other words, the best view in Japan (east of Korea, where the sun rises) he had ever seen. His exact quote is displayed on a plaque right above the same window where he looked out when he visited during the Joseon Dynasty.

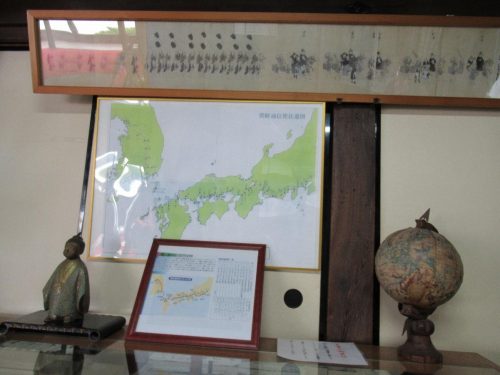

Taichoro has a history of hosting envoys from Korea, evident from the artifacts and artwork that remain in the hall. In addition, the hall also features maps detailing the path the Koreans took within Japan to reach the capital, and even a miniature model of what the procession would have looked like back then. Posters on one of the walls advertising contemporary Japan vs. [South] Korea sports events illustrate that the two civilizations are timelessly intertwined.

Further in the back by the prayer hall (where photography is prohibited), I found this neat, encased telescope pointing out the aforementioned window. Looking through the lens affords one a view of the Tahoto Pagoda on Bentenjima. The sign beside the telescope also encourages visitors to try aligning their camera lenses with the telescope lens for a most amusing photo.

If your camera and the telescope are perfectly lined up, this is the picture you get.

Under the Sea

I put my shoes back on at the entrance and went back down to sea level, walking through narrow streets and passing by old-timey stores selling frozen treats, tea, and homeishu, a medicinal liquor with origins in Fukuyama. At the end of the road was the Joyato Lighthouse, a symbol of Tomonoura itself and a highly popular photo spot. The old lighthouse juxtaposed with a group of old-timers sitting and casually chatting the day away evoked a sense of yesteryear, something not typically found or shown in mainstream tourist sites in Japan.

Speaking of the past, right next to the lighthouse was the Irohamaru Museum, which tells the story of the Irohamaru incident, in which the ship collided with a shogunate vessel and sank to the bottom of the Seto Inland Sea. According to the sign on the front of the building, Ryoma Sakamoto was onboard, and he and his crew recuperated at Tomonoura while Sakamoto sought monetary compensation for the losses. Naturally, this means the museum also doubles in serving as a biography for Sakamoto himself, and also mentions aspects from his life before and after the incident.

Inside the museum, there were pictures, videos, and even a life-sized model set illustrating how the collision went down, as well as how a team of divers found the wreckage on the seabed and retrieved artifacts from the Irohamaru.

Replicas of some of the objects that were actually onboard when the Irohamaru sank included jugs of liquor, Sakamoto’s personal revolver, and a rudimentary Japanese-English dictionary used by sailors at the time, rife with pronunciation errors.

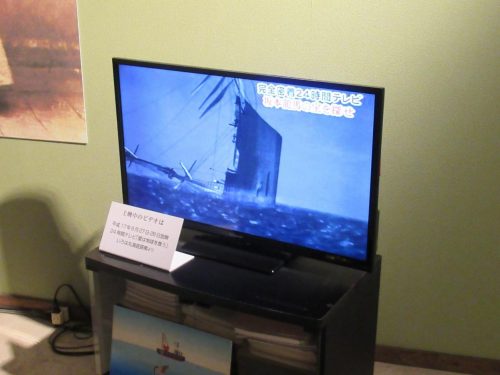

On one television monitor by the entrance (pictured below), there was footage from a TV show that simulated the collision and showed the painstaking efforts involved in diving down and finding the wreckage. On another TV (not pictured) to the right of the above display cases, episode 42 of the NHK drama “Ryoma-den,” which was about the Irohamaru incident, played on an endless loop. I stood in front of that monitor for over 45 minutes to watch the whole episode, and since there were no English subtitles, allow me to offer a brief synopsis.

On May 26th, 1867, the Irohamaru, en route from Nagasaki to Osaka, collided with the Meikomaru, a much larger vessel, in the middle of the Seto Inland Sea. Ryoma Sakamoto and everyone else on board survived, but the ship and cargo all plunged to the bottom of the sea, which meant astronomical financial losses. They regrouped at the port of Tomonoura, where most wept for the Irohamaru, but Sakamoto was intent on confronting the ones responsible and making them pay. There was a series of lengthy legal discussions between the owners of the two ships involved, but he finally got the reimbursement he desired thanks to a British admiral named Henry Keppel.

Sakamoto and Keppel both appealed to the International Common Law of Navigation (万国公法 – ばんこくこうほう) for their case. According to Keppel, collisions can happen at sea anywhere in the world; thus, those involved in and responsible for the incident have a duty to come to a consensus regarding reparations. He declared that the Irohamaru incident shall be judged like any other maritime collision in accordance with the International Common Law of Navigation; if not, Japan would not have the recognition and respect from her industrialized peers in Europe, Russia, and America. Upon hearing this, the Meikomaru’s owners felt they had no choice but to comply, and begrudgingly reimbursed Sakamoto’s party for their sunken ship. However, from then on, there were increased attempts on Sakamoto’s life, and at one point, he had to hide in a secret room in one of Tomonoura’s houses. That house—the Masuya Seiemon House—still exists as a museum and I would’ve toured it myself, but in a twist of cruel fate, it was closed that day for inexplicable reasons.

However, fate was not as cruel as I had thought, for on the second floor of the Irohamaru Museum was a model of Ryoma Sakamoto himself, hiding in a dim, concealed chamber and trying to avoid assassins until his premature demise on December 10th, 1867, a meager 198 days after the sinking of the Irohamaru. This building may not be where the man actually shut himself in, but it paints a sufficient picture in one’s mind and makes up for the other museum being closed. Off to the side by the window were some costume props; visitors were encouraged to put on the robe and sandals to have a historical photo taken with Sakamoto in hiding.

Personally, as I’m not much of a beach guy, my idea of a fun Marine Day is to visit the aquarium or hit up a historical port town for a taste of tradition and engaging stories like the Irohamaru incident. While most of Japan scrambles to modernize, small towns like Tomonoura remain old as they are, and in my humble opinion, it’s better that way, because when events of historical significance happen in said towns, the towns themselves become history that ought to be preserved. It’s that authenticity and sense of nostalgia that draws in the tourists, who wish to temporarily escape their modern lives by grasping at a period that ebbs away day after day. Whereas Onomichi attempts to renew its appeal with constant renewals and grand openings of trendy businesses, Tomonoura relies on its tried-and-true rustic charm to keep guests flowing, and while that may not always work in Tomonoura’s favor, this fisherman weathervane by the Tomonoura bus center (where I first arrived) sums up my thoughts succinctly.

Life is like the ocean; sometimes the tide is high, and sometimes it is low, and if the water level is disadvantageous now, then you just wait for a while and it will turn around. The above fisherman catches fish vigorously as the wind blows, and though he catches nothing when the air is calm, all he does is wait until he can. In case you haven’t caught on, I am alluding to Tomonoura’s tourist numbers and revenue, which have fallen as of late but will rise yet again in subsequent years. The charms of Onomichi and Tomonoura working in tandem make the Bingo area quite the alluring destination for visitors to Hiroshima Prefecture, and I sincerely hope that the eventual opening of Japan’s floodgates to the rest of the world will bring a wave of tourists to these quaint ports. Whether you seek something old or new, the tides of Bingo will yield discoveries for all, but it’s on you to make that voyage to see what intangible treasures await!

Written by the Joy in Hiroshima Team