100 Stories

Showcasing Hiroshima’s Noodles: Ramen Barely Scratches the Surface

Nowadays there are few who don’t know the ubiquitous, affordable delicacy that is ramen. The noodles originated in China and were introduced to Japan, but the dish has since become world-famous and loved by tourists all over the world stage, many of who flock to Japan to taste the real deal. In addition, ramen recipes vary all over Japan, with Tokyo’s featuring a soy sauce-based broth, Fukuoka’s making theirs with tonkotsu (pig bone) broth, and Sapporo’s incorporating miso into their soup. Unsurprisingly, Hiroshima has its own way of preparing ramen, but also goes the extra mile in innovating other ramen-inspired noodle dishes. There are a variety of ways to indulge in ramen noodles, such as serving them with toppings but without soup, or putting the broth on the side for the diner to dip and chow down, bite by bite.

Since ramen is such a staple dish in this country, would-be customers may suffer the problem of too many good candidates when selecting an establishment to try. Visitors to Hiroshima may be lost in a sea of choices for lunch or dinner even after narrowing options down to noodle restaurants, so to ease the decision-making process just a little, I took the liberty of scouting out and reporting on four places based on taste, local reputation, and exclusivity to my Home Sweet Hiroshima. Consider it a starter guide to some of the best noodles this city has to offer, all within reach from the city center.

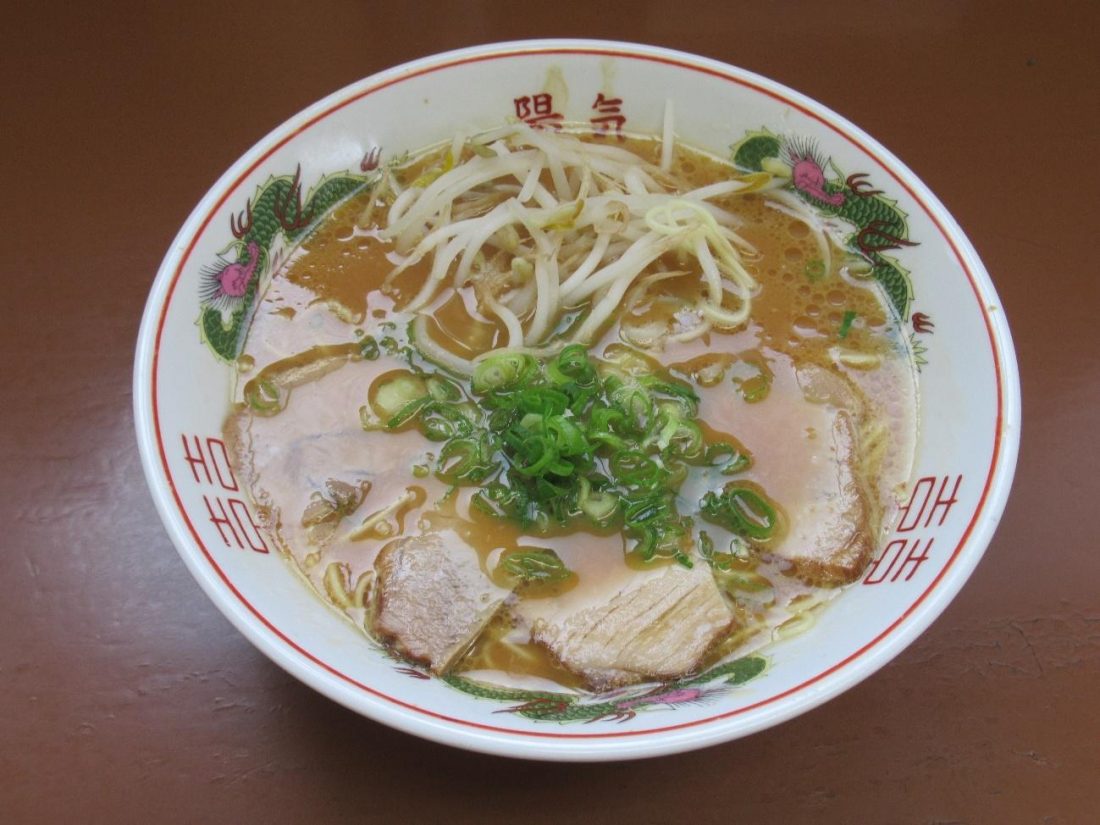

陽気 (Youki)

I’ll start with the store farthest from the heart of the city, but still readily accessible via streetcar. From Hiroshima Station or downtown, get on a number 6 streetcar bound for Eba, and ride it all the way to the end. After getting off, take the nearest crosswalk and continue south past an extremely wide and busy street. Keep walking until you see a tunnel in the distance and a fork in the road with a path stretching out ahead to the right. If you take the path on the right, you should eventually walk past a supermarket on your right and come to another intersection. Turn left here and keep an eye out for Youki (pronounced “yo-key”) and its conspicuous red awning.

This restaurant keeps it simple; there’s only one item on the menu, and if you don’t order it, the staff will beat you to the punch and whip up a bowl of Hiroshima ramen posthaste. The server caught me off guard with my meal in her hands before I even got a chance to sit down! The ramen here looks pretty typical with all the ingredients that should be there–sliced pork, bean sprouts, green onions–but looks can be pleasantly deceiving. I buried the bean sprouts deep in the bowl to cook them longer and soften them, and then dug into the noodles. The texture was so tender and fresh that I could’ve sworn this restaurant also doubled as a noodle factory, and lo and behold, Youki actually produces ramen kits in sets of three so that customers can replicate the same, beloved taste in the comfort of their own homes.

This restaurant actually made the list for “Top 100 Ramen Restaurants in Western Japan,” and was the only establishment in Hiroshima Prefecture to do so. If fact, Youki has so much renown that there are other branches throughout the city, like the one right off of Peace Boulevard just east of the Peace Memorial Museum, or the store next to Enkobashi-cho Station when taking the streetcar. However, visiting the granddaddy of them in Eba is a different experience altogether due to a nearby point of interest: Ebayama Park.

When I was approaching approaching Youki, I was met by a white sign pointing to the Ebayama Museum of Meteorology. I decided to walk off my dinner by going up that path to Ebayama Park, which is situated on the same hill that the tunnel from before cuts through. Ebayama Park is fit for a post-meal stroll, as the grounds are spacious and the incline isn’t as steep as other hills in the city. They have some interesting works of art, like this mother-and-child carving and public restrooms that look like they came out of some medieval fantasy world. Past this sculpture is a lookout point where one can gaze towards the Marina Hop, where the naked eye can still make out its Ferris wheel and docked boats in the distance. There are several benches here, so it makes for an ideal relaxation spot whether one is traveling alone or as a group.

I doubled back onto the main path and made my way past the fantasy toilets, a man practicing sports on the field, a playground, and a fancy French restaurant before finally reaching the Ebayama Museum of Meteorology. At this point in time, the museum was closed for the day, but the sign to the right of this edifice caught my attention. It read that it was once known as the Hiroshima Local Meteorological Observatory and survived the atomic blast on August 6th, 1945, retaining its original appearance to this day. I guess the museum doesn’t have to be open to teach me a thing or two, huh? After a few more paces, I reached a Buddhist temple called Ryukoin and took a gander past the fence, pleased by what I saw.

Moment of Joy: Ramen-iscence

From Ryukoin I could see the azure sky above, the deep blue Seto Inland Sea below, and a view all the way to Ujina Port in the middle. It was the type of scenery that could have one lost in one’s thoughts all alone, reflecting on the day’s event or just life in general. I found myself reminiscing on how well I’ve gotten to know my city with all the trips I’ve taken within it up to this point, which brought me a sense of jubilation and an eagerness to become even more familiar with it in the future. With a detour to Ebayama Park eating up quite a bit of time, a trip to Youki can feel like a vacation within a Hiroshima vacation.

尾道ラーメン 暁 (Onomichi Ramen Akatsuki)

When it comes to ramen in this prefecture, the Onomichi variant is even more famous than the Hiroshima variant on a national scale. Onomichi Ramen Akatsuki is a restaurant chain that was founded in Onomichi but weighed anchor in Hiroshima City just a few years back. There’s a branch in Teppo-cho just two blocks north of LABI Hiroshima, and another one in Komachi less than a ten-minute walk south of the Andersen bakery on Hondori. For dinner tonight, I’ll be stopping by the Teppo-cho branch to get a taste of Onomichi’s prized noodle recipe.

Ramen is what I’d call an ethnically confused food; the Chinese associate it with Japan and the Japanese seem to in part regard it as Chinese cuisine. One reason why is probably that the majority of ramen joints in Japan also serve up Chinese dishes such as fried rice and gyoza (pan-fried dumplings). Onomichi Ramen Akatsuki serves up ramen by itself or as part of a set that comes with fried rice, karaage chicken (another ethnically confused food), or both. I decided to fill my belly with a classic ramen and fried rice set, both of which were prepared to order and placed in front of me minutes later.

The Onomichi ramen came in a bowl of hearty soy broth with blobs of pig fat floating in it for extra flavor. There’s also a spicy version (pictured up top) available for an extra fee, but I held back tonight since I wanted to be able to drink the soup. On top of my noodles were some sliced pork, green onions, and marinated bamboo shoots that provided a welcome change of flavor and texture throughout the meal. The fried rice also complimented the noodles well, and a dash of black pepper to either does wonders. The round, smooth noodles make them easy to slurp up, and after ingesting all the solid food, topping it off with the broth hit the spot.

キング軒 (King-Ken)

This next dish is more like a distant cousin to ramen, but still based on an authentic Chinese recipe. King-Ken specializes in a dish called shirunashi tantan-men, or soupless dandan noodles. The Japanese spin on these noodles is a rather recent phenomenon, and according to gourmet magazine “dancyu,” shirunashi tantan-men can be roughly divided into three types: Chengdu-style (named after the city of origin and staying truest to the original form), Tokyo-style (incorporating more sesame paste and toppings like dried shrimp), and Hiroshima-style (which doesn’t skimp on the mouth-numbing spices). Additionally, what’s special about this dish in Hiroshima is that we have an abundance of restaurants dedicated solely to shirunashi tantan-men, whereas in other parts of Japan, it’s only one of many items on the menu and ends up being overshadowed by other Chinese-style dishes. To get to King-Ken from Hondori, turn left at Yoshinoya, walk one block south, and turn right.

Customers entering the store will first order from a vending machine and present their tickets to the chef before sitting down. They have several versions of shirunashi tantan-men with different kinds of toppings, so my health-conscious self went for a bowl with a mound of veggies on top. When my food was served, I couldn’t even see the noodles beneath all the leaves, so I got straight to mixing. I knew it would look and taste a lot better after the flavor was uniformly distributed across the noodles and salad.

King-Ken recommends that diners mix their noodles at least thirty times before digging in, or until the hot oil, powdered pepper, soy sauce, sesame sauce, and ground meat miso virtually disappear. I tried my best to stir without letting any of my greens fall out, and I’d say I did a decent job since I managed to coat all the vegetables in the spicy mixture with no liquid remaining in the bowl. Hiroshima-style shirunashi tantan-men is plenty spicy on its own, but for those who insist on more kick, a pepper container is ready on the counter so customers can bring as much heat as they want. For an additional fee, customers can also order a soft-boiled egg in a separate dish, wherein the egg is beaten and used as a dipping sauce for the piquant noodles, just like in sukiyaki. To finish off the meal, diners can also order a separate bowl of white rice to soak up any remaining sauce (waste not, want not) and ensure a full belly.

ばくだん屋 (Bakudanya)

When I eat ramen, I strive to enjoy both the noodles and the broth together, but some decades ago, some great minds had the idea to serve them separately, with the toppings either in the broth or on top of the noodles. This recipe is known as tsukemen, and the noodles are to be dipped in a separate bowl of broth before being eaten. In most parts of Japan, the broth is just a stronger version of typical ramen broth, but in Hiroshima, it’s a red, hot dipping sauce. There are a variety of eateries in the city dishing out this variation of tsukemen, but one tried-and-true local favorite would have to be Bakudanya. The main store is in Shintenchi across from Don Quijote, but I hit up another branch in Dobashi, which is still easy to get to from Peace Memorial Park.

First, cross the bridge just south of the Atomic Bomb Dome and go west until you come upon the green Honkawa Bridge. After crossing the bridge, keep going west past a supermarket on your left until you hit a busy road where the streetcar runs by. You should see Bakudanya right across the street.

Bakudanya serves several different kinds of noodle dishes, but the Hiroshima-exclusive spicy tsukemen is what I’m here for. Once again, I got a healthier version with extra vegetables, so my order came out with only two slices of pork, but big piles of cabbage, green onions, and shredded cucumber, accompanied by the dish of broth with sesame seeds floating inside. Customers specify their desired level of spice on a scale of one to eighty; the default is level two but I went for level four.

If you ever find the broth is not spicy enough, just tell the chef and he’ll add more hot sauce, free of charge. There’s also a bottle of sesame seeds on the counter you can use to refill your dish. The sesame seeds add flavor to every bite you dip into the broth, and they’ll go quickly, so you’ll probably be using that bottle pretty often.

When one mentions ramen, not too many visitors to Japan think of Hiroshima, but the above establishments and recipes are a testament to Hiroshima’s ability to compete in the ramen scene. Good ramen and other noodle dishes can be found anywhere in Japan, but when you swing by Hiroshima, make an effort to taste the exclusive wonders that are Hiroshima ramen, Onomichi ramen, Hiroshima-style shirunashi tantan-men, and Hiroshima-style tsukemen! The way ramen and related dishes evolve as they migrate shows that ramen is most certainly not a food that is confined to a single country or culture. Though ramen may conjure up images of Japan, at this point I don’t even consider it a fully Japanese food. Instead, it has become a universal meal that has taken over the hearts and stomachs of diners worldwide.