Now & New

Higashihiroshima Music Festival: The Artistic Sides of Saijo

Throughout my adventures across Hiroshima Prefecture (including some journeys into neighboring ones) I try to cover the seasonal sights and events of every municipality in the Hiroshima area, going east to places like Mihara and Fukuyama, west to the small towns of Otake and Iwakuni, south to islands such as Okunoshima or Ikuchijima, and north to the mountainous regions of Sera and Shobara. Much to my dismay, one city that tends to drop off even my radar is Higashihiroshima, Hiroshima City’s easterly neighbor. Higashihiroshima—in particular the Saijo area—is famous nationwide for its Sake Brewery Street, and locally renowned for being a university town (the bulk of Hiroshima University’s facilities are here). For foreign residents of Hiroshima, Saijo is remembered as the place where most of us commute to take the Japanese Language Proficiency Test (JLPT) held twice a year, which regrettably may negatively impact our impression of the city.

However, Saijo, being the university town that it is, indubitably has an artsy-fartsy side rich in history, with plenty of museums and performing venues to boot. Over the course of June and July, there was the Higashihiroshima Music Festival, held over various weekends in public spaces scattered across Saijo. Regrettably, the rain caused the cancellation of some outdoor performances, and since a lot of the most anticipated events required reservations (to be done in Japanese with an address in Japan), I will instead focus on artistic aspects of Saijo that any visitor to Japan can enjoy. This world is filled with art—even if it isn’t intended to be art—in the form of everyday life, from old buildings to local food, and if tourists know where to find this mundane art, a visit to Saijo at any time of the year can be a culturally enriching experience.

The Art of History

The history of this town is richer that one would initially think, with sites dating back as far as the 5th century. I started my tour of Saijo by delving into said ancient history at the Mitsujo Kofun burial mounds, which can be reached via a 10-minute bus ride from Saijo Station. Those who cannot make a #2 bus that stops in front of the mounds can opt to take a different bus line that stops at Chuo Toshokan-mae (中央図書館前 – “in front of the Central Library”) and walk about seven minutes to the site.

Considering that I visited in the middle of the rainy season, I was taking a gamble with my trip to Saijo, but I won that day. The Mitsujo Kofun is composed of three mounds, the largest of which is keyhole-shaped (on the left), this one being the largest keyhole-shaped mound in all of Hiroshima Prefecture. Tumuli such as the ones found at Mitsujo were used to bury the ancient Japanese elite and royalty, and replicas of the pottery excavated from the site were lined up neatly along the perimeter and paths of the largest tumulus.

It may be difficult to ascertain the shape of this mound from close up, but once on top it was easy to see that it had a square front end and a round back end, hence the keyhole shape when viewed from the sky. At the round end of the tumulus, there were two glass windows showing the excavated graves of the entombed, which looked big enough to fit an average Japanese person from the present day. A staircase just past this exhibition provided a short path from the first tumulus to the second.

From the top of the second mound, I was fed a useful tidbit of information from a local guide. If one climbs halfway up the staircase of the second (green) mound, faces the first (keyhole-shaped) mound and loudly claps one’s hands, a squeaky echo reminiscent of a rubber duck can be heard. Researchers have yet to uncover the secret behind this acoustic phenomenon, but I—who have been told I have a deafening clap—particularly relished in creating cutesy sonic booms between the tumuli.

After checking out the most ancient tourist site in Saijo, I made my way towards another antiquated wonder near Saijo Station: Aki Kokubun-ji. Long ago, around the seventh century, Japan was organized into provinces, one of which was named “Aki (present-day Western Hiroshima Prefecture),” with its initial capital close to Saijo Station. Every province had a principal Buddhist temple—actually one for monks and one for nuns, so two—in the provincial capital called a kokubun-ji (the one for monks), so Aki Kokubun-ji was once the most important temple in the Hiroshima area. Even after the provincial capital was moved to Fuchu Town—today an enclave inside Hiroshima City—Aki Kokubun-ji held onto its prestigious status until the province system was abolished in the Meiji era in favor of having prefectures. This can be seen from its spacious grounds, as this temple with its remains of edifices no longer standing is actually larger than meets the eye. On the day of my visit, some ceremony was going on inside the main hall, and I was lucky to catch one of the monks leaving whilst carrying a tray of containers probably used in some ritual.

The Art of Gastronomy

Following my tour of traditional burial sites and temples was a traditional Japanese lunch in town. I stopped by a fancy kaiseki restaurant called Nozomi (希味 – “the taste of hope”), which is normally only open for dinner, but also serves lunch upon reservations by phone. The staff warmly welcomed me as I stepped into the restaurant and directed me to a seat with the table already set for a multi-course meal. Soon enough, I was presented with a tray full of starters, just like in a miniature kaiseki course. Clockwise from the left, I was served: marinated fish topped with a leek, chawanmushi (a savory egg custard with chicken, shrimp, and mushrooms inside), a green salad with Caesar dressing, macaroni salad garnished with salmon roe, and the quintessential Japanese pickled radish.

Before even finishing all of the above dishes, the main course arrived, as presentable as I expected it to be. I got a platter of sashimi featuring four species of fish as well as the blood clam, paired with soy sauce, wasabi, a perilla leaf, and even an edible yellow flower! That was followed by some tempura of shrimp and local vegetables, which were a stellar combination with the salt provided. To top it off, these entrees were served with fish-flavored steamed rice, and there were free refills to boot.

As stated above, Saijo is famous for sake, so after lunch, one can go sake tasting at the numerous breweries along the Sakagura-dori. If alcohol isn’t your thing, you can still learn some history by touring a brewery like Kamotsuru and enjoy looking at the old buildings in the area. This red brick smokestack that belongs to Kamotsuru is a must-snap photo spot for all tourists to Saijo.

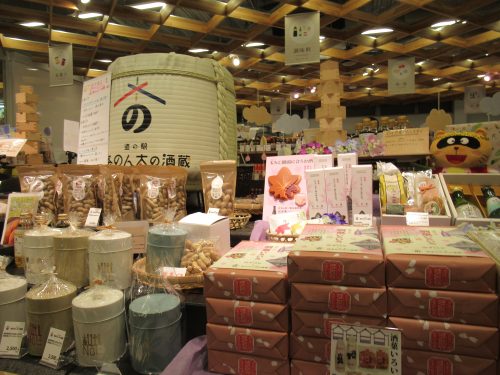

As for Saijo food souvenirs besides sake, look no further than “Michi no Eki Saijo Nonta no Sakagura!” This local souvenir wonderland is but a 13-minute drive from Saijo Station, but being a highway stop, it’s kind of difficult to access without a car. Those who won’t drive, take a taxi, or sign up for a bus tour that takes them to Nonta no Sakagura should take a bus from Saijo Station bound for Hachihonmatsu, get off at 磯松団地 (いそまつだんち – Isomatsu Danchi), and walk southwest for approximately 22 minutes before reaching the rest area. This entire facility—which contains a gift shop, restaurant, kids’ play area, and more—is dedicated to Nonta, the mascot for Saijo. Lots of Saijo delicacies were displayed at the front, including sake-flavored foods, snacks that pair well with sake, and bites that were served to the G7 world leaders back in May.

Moment of Joy: The Art of Whimsicality

Between finishing my lunch at Nozomi and touring Sakagura-dori, I dropped by the tourist information center upon learning that one of the many concerts of the Higashihiroshima Music Festival would be held on the second floor of the building that day. Luckily, this event was free and there was ample seating available, so I quietly plopped myself on a stool and awaited the next piece from the performer on stage. The musician had some whimsical musical contraption at her fingertips that resembled a piano, but distractingly colorful and laden with children’s toys whose sounds she used to enhance her playing. The resulting tune was unlike anything I had ever heard at a concert, and although I was dumbfounded at what my ears heard, I was delighted to have discovered such a clever, artistic use for toys.

The Art of Performing

Speaking of the music festival, the most anticipated events were ones that required registration (I was too late by the time I found out) and were held in dedicated venues like the Higashihiroshima City Museum of Art or the Higashihiroshima Art and Culture Hall Kurara. On the 8th of July, the JGSDF had a concert at Kurara, but I was denied entry and for all I know, photography may have been prohibited anyway, so I figured it was better to showcase the venue when empty, something that can be seen when booking a private tour. Concert halls certainly look different from the other side when tourists have the opportunity of standing on stage, pretending to be stars.

This exact theater was featured in the Japanese drama Drive My Car, which was explained through informational posters displayed on stage. The tour guide not only let us pose for photos on stage while he spoke of Kurara’s fame, but also demonstrated the workings of the curtain and other backstage technology before taking us off stage into the hallways exclusively reserved for performers and staff. This hallway had several backstage rooms for actors to await their time to shine, as well as plentiful storage space for state-of-the-art equipment and musical instruments, such as this Steinway & Sons grand piano. The central air conditioning system and adjacent devices maintain the perfect temperature and humidity inside the storage room to ensure that the wood and metal parts never rot or rust.

The Art of Preservation

While on the topic of preserving previous musical instruments, Saijo goes beyond merely preserving things and aims to embalm history itself with how it carefully protects, restores, and displays its archaeological paraphernalia in museums. The Higashihiroshima City Museum of Art right across the street from Kurara is a prime example, as the earthenware dug out from the Mitsujo tumuli were painstakingly reassembled and placed into the permanent exhibit on the second floor. Many of the items on display came with bilingual (Japanese and English) plaques, and beside them were pictures of the Mitsujo mounds as they were being excavated.

In the first-floor lobby of the museum were these two abstract statues, which look like beasts to me, but honestly, I’m not sure what they actually represent. The first floor also houses the gift shop and a roomy rest area, where yet another concert was held on the 8th of July as part of the Higashihiroshima Music Festival. This museum, Kurara across the street, and the plaza between them altogether make up a grandiose public space for students and families to appreciate nature and the fine arts in their everyday lives.

The next time you think of Saijo, try to conjure up images beyond alcohol consumption and tertiary education. Just because a town is small doesn’t mean by any means that there is a lack of things to see and do. There may be more museums in Hiroshima City or even Onomichi, but Saijo demonstrated full well that one doesn’t need a museum to see art, for there is art to be witnessed in all facets of one’s daily lifestyle. The Higashihiroshima Music Festival was especially influential in drawing my attention to the city’s tourist sites (even though I barely got to see any concerts), but now I’m determined to return next year to guarantee that I will see my fair share of shows. Anyone—tourist or resident—who has time to pay a visit to Saijo ought to come for the sake culture but stay for the art in all its forms.

Written by the Joy in Hiroshima Team