Now & New

Traditions of Ebessan: Autumn Festivals in Full Swing

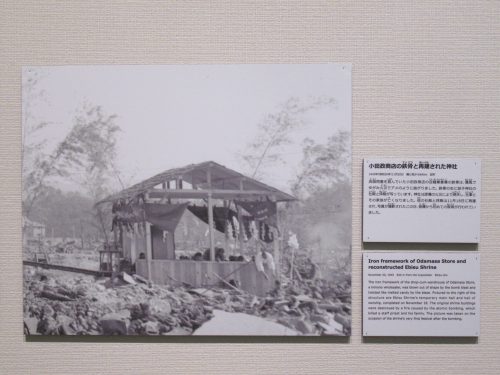

Autumn is as good a time for festivals as summer, as can be seen from the Ebisu Festival (often shortened to “Ebessan”), the last of the Three Great Festivals of Hiroshima City. Like its brethren Toukasan and Sumiyoshisan—held in June and July, respectively—Ebessan is also centered around a shrine in the city: the Ebisu Shrine in Hatchobori, deep in the heart of Hiroshima’s bustling entertainment and nightlife district. The Ebisu Shrine, located on Ebisu Street, was established in 1603, and the festival that honors Ebisu, a Japanese god of fortune, fisheries, and commerce, has been held at that shrine every single year since its founding. In fact, Hiroshimarians are so adamant about celebrating it every autumn that even after the city center of Hiroshima was vaporized on the 6th of August, 1945, an impromptu shrine was built 840 meters from the hypocenter on the 18th of November and celebrations commenced immediately.

In modern times, Ebessan continues to dazzle the citizens of Hiroshima, and even during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021, the festival wasn’t canceled outright, but rather scaled down to minimize the risk of infection. 2022 marks the first time in three years that Ebessan was held at its usual scale, and as per standard procedure, the festival lasted from the 18th to the 20th of November, regardless of weekdays or weekends. I dropped by on the second and third days of the festival, which just so happened to be Saturday and Sunday, meaning I was prepared to be swept into a river of locals.

Strolling the Streets

Although the Ebisu Shrine is the hub for all of Ebessan, the festivities and festival stands stretch out toward Peace Boulevard along Chuo-dori, which bisects Ebisu-dori on which the shrine is located, and countless other stands run along Kinzagai and even wrap around the west and south sides of the Parco main building before the path merges with Chuo-dori. I started perusing the stands from the northern end of Kinzagai near the streetcar stops and wound down in the direction of Parco before snaking back up to Ebisu-dori. There were signs every few meters displaying the name of the Ebisu Festival, red lanterns with the names of sponsors printed on them, and ambient music on loudspeakers to get everyone into that traditional autumn festival mood. From the western segment of Ebisu-dori, I crossed over Chuo-dori to the area where the shrine was.

Ways to Pray

Past Yamada Denki on the left and Daiso on the right, there were various shops and restaurants lined up, some of which put out temporary tables to compete with the festival food stands and try to earn a little more over the three days of Ebessan. After a few more paces, I came upon a line of people, undoubtedly waiting their turn to pray at the Ebisu Shrine. There was a gentleman always holding up a sign to indicate the end of the line so people know what the line is for and that there would be no accidental cutting in line. I have stood in line to pray during past Ebessan, but today I was content in simply watching others do it instead, so I progressed around the line to the shrine itself to check out the action.

Worshippers would bow before the shimenawa straw rope, then proceed to the shrine altar to pray and be blessed by the priests inside. However, when I participated five years ago, there was one priest with a gohei (御幣), or a Shinto wooden wand with paper streamers, who blessed visitors by rubbing the tops of their heads with the steamers as they bowed their heads to the god Ebisu enshrined within. The worshippers then left through a separate exit in order to keep traffic smooth, and were welcome to purchase omikuji (御神籤), paper fortune slips that indicate how prosperous they would be from here on out.

The fortune outcomes vary from 大吉 (だいきち – very lucky) to 凶 (きょう – unlucky), with other outcomes like 中吉 (ちゅうきち – moderately lucky) and 末吉 (すえきち – lucky in the future) in between. Whether the fortune was desirable or not—but especially if one draws the unlucky fortune—people tend to tie their fortunes to the above bamboo rack to strengthen the effect of the blessing or put distance between themselves and the curse. There’s a simple, traditional way to fold and tie the paper to the rack that seemingly every Japanese person knows, elucidated in the video below.

Right beside the rack of fortunes was this gargantuan wooden barrel where people threw in money to curry favor with Ebisu and ensure the fruition of their dreams. I was expecting nothing but spare change when I peeped inside, but people threw bills into the barrel as well. My guess is the shrine staff figured that with an average of over 300,000 people visiting over Ebessan every year, the money adds up, and not having to empty the container is an advantage to the superfluous size. Smaller children may have to be lifted up to throw money or look into the barrel, but if anybody falls in, it may be a challenge to climb back out.

Snack Shacks

The fare on tap at the food stands all over the festival site was for the most part just your standard carnival cuisine: karaage chicken, frankfurters, French fries, candied fruit, baby castella bites, the list goes on. Everything looked yummy, and some of the most popular items had long queues sprouting from them, inadvertently impeding foot traffic along the sidewalk, blocking access to adjacent stands, and even confusing would-be customers as to what queue was for what stand.

Allow me to give a few tips to have the least hectic time at festivals like these. If going with friends, family, or other companions, be sure to hold onto said companions when wading through the river of people. When grabbing onto somebody’s clothes or bag, it makes it harder for the group to get separated, but at the same time, a line of people holding onto each other may be an obstacle for others trying to navigate the crowds, so please be mindful and grab hold only when necessary. Also, once you’ve bought something to eat or drink and wish to enjoy it on site, it may be wise to duck into a corner or storefront to savor it uninterrupted. Finally, be sure to look at the floor from time to time, as there may be items dropped by yourself or somebody else, or spilled food and beverages that may cause you to slip or make your shoes sticky and gross.

There were quite a few products of note for sale amongst the stands, such as character-themed goods to be bought or won from a game. One stand east of the Ebisu Shrine had these character-shaped lollipops, which were cute and accurate, and the store even kept up with modern times by accepting QR code payment methods. Speaking of characters, though, the most amazing food stand in all of Ebessan would have to be this hard candy artisan, who writes people’s names or just about anything else in Chinese characters using melted candy.

The price of the treat varies with how many characters he traces with liquid candy: the base price is ¥500 for one symbol, then at additional ¥100 for each additional symbol up to a maximum of four symbols. Besides Chinese characters, he can also draw candy pictures for a fixed price of ¥800. Each character is written in cursive as one, continuous stroke with a heart attached somewhere at the end, and when he finishes his work, he pushes a wooden onto it and voilà, an instant lollipop wrapped in plastic to go!

After what seemed like hours of aimless pondering, I finally managed to scout out every single stand at the festival site and decide on my dinner for the night. There were so many food stands selling fried chicken in some form or another, but only a couple serving up the more exotic yangnyeom chicken, which is basically karaage chicken drenched in a Korean sweet and spicy sauce. Yangnyeom chicken from one particular vendor was available in regular and large sizes as expected, but there was also a “Dragon Yangnyeom” that was being advertised but not ordered by anybody. Out of curiosity, I gave it a go, then watched as the vendor stirred a generous amount of fried chicken in a bowl of yangnyeom sauce and squeezed ten pieces onto a single skewer. They barely fit on the skewer, which in turn barely fit into the plastic container they gave me, not to mention that the handle part of the skewer was covered in chicken!

Moment of Joy: Away from the Bustle

To complete my meal, I also got myself some roasted corn on the cob, and then made tracks away from Ebessan to a more tranquil location to eat. As I know my way around downtown Hiroshima, I figured that the nearest public place where I could have my dinner in unperturbed solitude was a skybridge passing over Aioi Boulevard (the main street where the streetcar runs) in Kaneyama-cho. Honest to goodness, my choice of dinner wasn’t the most financially wise (no festival food is), but I was certain that ten pieces of spicy Korean fried chicken with a side of corn would sate my appetite for the rest of the night. Tack on the splendid night view of Hiroshima’s cityscape, and I had myself a recipe for a picture-perfect way to end a day at Ebessan.

Miscellaneous Mementos

Of course, some festival goers want something besides their own memories and pictures of the event to remember their time downtown, and as far as physical souvenirs are concerned, Ebessan has those people covered. Among the many carnival-game stands available, visitors can draw lots, shoot targets, and scoop plastic balls out of water for an array of prizes ranging from plushies to full-blown video game software, depending on one’s skill and/or luck. Every player gets something for participating so there’s no feeling of regret when one loses; case in point, at a past autumn festival (not Ebessan), I drew the unluckiest lot available and still got an anime postcard as a consolation prize.

Those who want the fun and challenge to continue after going home can opt to scoop goldfish to take home as pets. This old-time activity is a hit with festival goers of all ages, as can be seen from this posse of middle-school boys having a good time. Taking part in these games is most enjoyable when with family or friends because the fond memories of playing together will without a doubt last longer than the lifespan of any fish or toys won from playing. For those who don’t wish to test their luck or skill at any carnival-game stand, there’s always the option of buying trinkets like plastic masks with the likeness of recognizable characters or inflatable mallets to goof off with in a less crowded area.

The one souvenir that can be bought nowhere else but at Ebessan would have to be the komazarae, which are lavishly decorated bamboo rakes sold in front of the Ebisu Shrine. In addition to praying to Ebisu personally and donating money into the enormous barrel, those who truly wish to rake in profits as it were tend to purchase one of these komazarae and display it in their homes or stores. I have personally seen these rakes inside the occasional restaurants, a reflection of the owners’ wish to draw in as many customers as possible and earn big bucks. Simultaneously, the more businesspeople who fancy these komazarae and buy them, the more those vendors make, and the more publicity Ebisu gets, so everyone wins!

It would be no hyperbole to claim that the history of Hiroshima’s festivals runs deep, with the 420th Ebessan that occurred this November. Come atomic bomb or novel coronavirus, we Hiroshimarians will celebrate in the midst of adversity, for these regular festivals are what keep the joy in Hiroshima and give us the strength to overcome any obstacle in our path. May I remind you that Ebessan is by no means the only autumn festival in Hiroshima, but only the most famous, lively, and most anticipated one. Other festivals at local shrines throughout the city abound, and that number increases when considering fall festivals all over the prefecture. If you drop by Hiroshima at any time in November, especially on a weekend, finding a festival should be as easy as watching maple leaves fall, so free up that schedule just a little bit and join the party!

Written by the Joy in Hiroshima Team