Now & New

Hiroshima’s Atomic Bombing Remembrance Day: Acknowledging Our Rebirth Following Obliteration

Hiroshima is one of the most famous cities in Japan, no doubt about it. Why it’s famous, however, depends on the person being asked. Most people in Japan—Japanese or foreign—conjure up images of oysters, lemons, the floating torii of Itsukushima Shrine, Momiji Manju, okonomiyaki, and much more. Outside of Japan, though, the first thought to surface in most people’s minds when they hear the name “Hiroshima” is almost always the atomic bombing that occurred 77 years ago. While the incident may be treated as an afterthought for those of us who live here, the significance of August 6th is etched into our minds as a heinous reminder of what exactly warfare is capable of producing, and the episode wherein Hiroshima’s city center disintegrated in a flash.

Every single Hiroshimarian has memorized the date of August 6th, 1945, the day our city became the first city on Earth to be hit by an atomic bomb. Naturally, what is now Peace Memorial Park is awash with events on that exact date every year in observance of the above tragedy. Concerts are held on Peace Boulevard and outside the Peace Memorial Museum, speeches by prominent world leaders are given close to the cenotaph, and protests occur right next to the Atomic Bomb Dome. Whether I have work or not on that day, I make an effort to drop by the area; the most significant moment would be at 8:15 in the morning, the exact time of the detonation.

Moment of Contemplation

Peace Park is a short walk from my place, so every morning on the 6th of August, I scarf down breakfast and walk straight towards the Peace Memorial Museum. Foot traffic around the area is so dense on this day that police block off cars from select bridges and cars leading to Peace Park. Fortunately, when approaching the south end of the park, the sidewalk is wide enough that visitors need not worry about having to squeeze past others on the way to the Peace Memorial Ceremony.

Thankfully, I made it on time this year for the moment of silence that takes place at exactly 8:15 at Peace Park. In past years, I had been on the way when the chime signaling the moment of silence rang; those away from but in the vicinity of Peace Park can hear it, and it is customary for people to cease what they were doing, stop in their tracks, momentarily shut their eyes, and bow their heads in silence for roughly one minute. Afterwards, in the square by the cenotaph further north of where I was, several important figures were giving speeches related to the atomic bombing. They’re always underneath a big tent talking to an audience sitting under an array of smaller tents, but one must be invited to these monologues so the tents are closed to the general public. I only ever got to sit and listen once in all the years I have lived here (I inadvertently snuck in after being mistaken for another invitee who didn’t show up), but this year, no dice.

Is Today Truly Peaceful?

In order to circumvent the roped-off section of Peace Park, I took an alternate route that led up to the riverside café and the western end of Hondori. Along the way, I saw some people carrying banners and wearing signs on their bodies advocating for quiet prayers for peace on this solemn day. This movement is in opposition to the racket produced by the usual protesters right by the Atomic Bomb Dome and adjacent scramble intersection, who capitalize on the occasion to bring attention to the issues of nuclear arms, Article IX of the Japanese constitution, and other contemporary events. These noisy demonstrators justify their actions on the grounds of freedom of speech and the right to organize and demonstrate, but no shortage of locals find their political parades a nuisance, and therefore have silently retaliated in the manner you see above. These were the exact same people who were distributing leaflets downtown on the days leading up to today; I decided that I would at least not contribute to the high-decibel marches of which they spoke. I continued north toward the Atomic Bomb Dome and soon discovered the exact rowdy protesters to they were addressing.

To sum it up, if it had been on the news recently, some people in the numerous waves of demonstrators were holding up a sign related to it. Every wave of protesters was flanked by police officers for the protesters’ safety as well as for the safety of the onlooking public; policemen directed foot traffic in this section of peace park and led all the noisy demonstrators down the street. To no surprise, a throng of silent counter-demonstrators was standing by the side of the street suggesting they keep quiet out of respect for this day of remembrance, but noise levels remained constant. Who would’ve thought that on a day when Hiroshimarians should be more peaceful than ever, that a conflict like this would occur in one of the most sacred parts of the city? On the other hand, compared to demonstrations that go on in Western and other Asian countries that expectedly erupt into violence, the movements that happened today looked rather calm.

Following the dispersal of the majority of the protesters, I made my way up past the Atomic Bomb Dome and looked left toward the banks of the Motoyasu River. Seeing a father enjoying a normal day at the park with his son was a fresh change of pace from the commotion going on further south, and closer to the notion of peace that this special day is supposed to invoke. Of special note was the boy’s shirt, reminding me that “life is like the ocean,” a statement with which I can agree on many levels. We all have calm days and stormy days, and since it’s only natural to cycle through calm and stormy times on a regular basis, it serves little to complain when waters are peaceful but boring, or even when the waves are turbulent and stressful. This is also how I view history on a grand scale; Hiroshimarians did not remain sad for all time on account of that infernal happening, but rather, serenely live out their everyday lives to this day while bearing that burden.

Case in point, have a look at this T-intersection on the Aioi Bridge, which is a segment of a much longer Aioi Boulevard. Due to the majority of the streetcar lines running through this wide street back then and even now, Aioi Boulevard is lovingly referred to as Densha-dori (電車通 – Streetcar Street). The T-shape of this intersection and the vital role it played in the city’s infrastructure made it an ideal target for the Enola Gay to drop Little Boy (the atomic bomb meant for Hiroshima) over the city that fateful morning. In a cruel twist of fate, the wind blew the bomb southeast through the sky, where it blew up right above the Shima Hospital, instantaneously annihilating everyone inside as well as obliterating everything within a 1.6-kilometer radius. In spite of all that, Hiroshima City rapidly recovered, and Densha-dori, the Shima Hospital, and other vaporized parts of town have gone back to operating as they were before the bombing, with people coming and going, their minds eagerly fixated on a brighter future.

Let Your Thoughts Flow

I had work on the 6th of August yet again, which meant I couldn’t be at Peace Park for most of the afternoon, and could only return close to dusk. On the bright side, my coworkers and I timed our visit right with the Peace Message Lantern Floating having barely started. This event had been cancelled in 2020 and 2021, so this year, throngs of enthused visitors were packed at both banks of the Motoyasu River to see paper lanterns being floated from boats in the middle of the river as well as from the bank opposite the Atomic Bomb Dome. Visitors can write their wishes for anything in any language on some colored paper, which is affixed to a wooden lantern frame, placed carefully on the surface of the river, where it floats downstream, carrying the thoughts of the writer to people worldwide and possibly the afterlife too. Obviously, those floating the lanterns from the boats are volunteers doing the job on behalf of those who wrote their wishes, and they make sure to leave plenty of space and time in between lanterns so that they don’t topple each other.

We were excited to be able to write our own messages of peace and hurriedly sought out the tent where we could sign up. Regrettably, when we reached said tent, we found out that our work shifts made us too late to register and design our own lanterns. On top of that, even if we had made it, we weren’t allowed to approach the riverbank due to COVID-19 so it wouldn’t be ourselves floating the lanterns. Those who wish to participate no matter what had the option of scanning the QR code on the sign and virtually floating a lantern down the river, but that’s just not the same.

Instead, we tried to get as close as we could to the riverbank where the event organizers were floating lanterns, in hopes of snapping the best pictures. Meanwhile, there was a band nearby playing somber, otherworldly music to accompany the floating lanterns. To see the Motoyasu River adorned with a spectrum of color on this momentous day made photos of the Atomic Bomb Dome much more beautiful than they typically are.

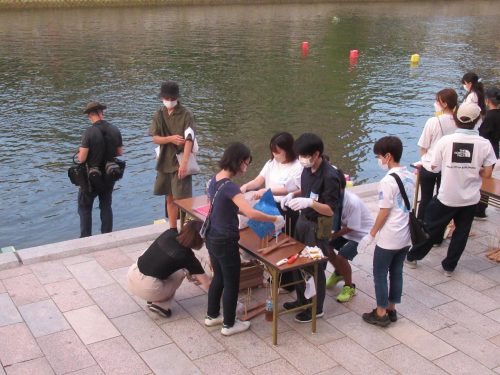

Speaking of lanterns, a legion of volunteers was down some blocked-off stone steps, assembling and floating the lanterns one after another. I looked on as each person meticulously fitted the paper tube over the frame and making sure the square shape was stable. Some professional photographers were also on standby, ready to take close-up pictures when the time came to float the lanterns.

The volunteer would first walk down to the surface of the water, cautiously position the lantern in the water so that it wouldn’t fall, say a quick prayer, and give the lantern a gentle nudge downstream.

Spectators on both sides of the river as well as way high up in Orizuru Tower were awestruck at the sight of so many glimmering lights drifting on the water. The lanterns got prettier as the sun continued to set, and this number of lights was a mere fraction of what would usually be put into the river. Rather than be disappointed at the few lanterns today that I couldn’t float myself this year, I was getting pumped up at the thought of subsequent Peace Message Lantern Floating Ceremonies!

Moment of Joy: Radiant Dusk

It wasn’t just the river that looked stunning at this hour, for up in the sky, the sunset put on a show of its own. I was inspired by a nearby tourist to take the below photo of Peace Park at sundown, which I believe was the most beautiful photo I took that evening. While we were a bit disheartened by not being able to participate in the Lantern Floating, we were determined to stick around and appreciate the radiant, orange sky until it got dark. It was a picture-perfect way to end the day and commence the good times of a Saturday night in town.

Power of the Tower

If there’s ever a day to ascend Orizuru Tower, it would be the evening of August 6th, to not only see the Atomic Bomb Dome from a unique angle, but to get a bird’s eye view of the Lantern Floating too. I went up to the observation deck on that exact date last year expecting to see at least a few lanterns waltzing on the Motoyasu River, but got dead squat. Just take this picture and imagine the river in the foreground dotted with the lanterns from before.

It’s not just gazing down, though, as Orizuru Tower puts on an after-hours Rooftop Bar on its thirteenth (observation deck) and twelfth (interactive exhibit) floors from June to December, complete with engaging music and comfortable seating. They charge a fixed admission fee to go up to the top and only ask that customers order one food or drink item each to enjoy while relishing Hiroshima’s cityscape. You may not be able to see as much with a dark sky, but city lights combined with the cube lights and bottled lights at the Rooftop Bar can be just as romantic.

What’s more, the Rooftop Bar has an extensive variety of cocktails (alcoholic and non-alcoholic) that are rotated seasonally, as well as the usual beers, wines, and spirits that are popular at any bar in the city. No need to worry about the draft up here either, because the staff loan blankets to customers during the colder months so they can be cozy until closing time, which is 11:00 p.m. or midnight, depending on the day. If you have the privilege of visiting Orizuru Tower on the evening of August 6th, just pop a squat anywhere with your fancy drink and stare pensively into the distance as you contemplate deep things like future plans or world peace.

Hiroshima’s Atomic Bombing Remembrance Day is not at all a public holiday (some schools actually make students participate in something peace-related even though it’s their summer break), nor is it a day for merrymaking, but that doesn’t mean it has to be a sad occasion. Peace means different things to different people as I saw today: it could mean quietly praying, organizing a march in public, taking your son to play at the park, working free from the fear of an atomic blast, lighting lanterns to float down the river, or partaking in a drink with some bar bites atop a tower. Tourists from the outside almost always visit Hiroshima with thoughts of the atomic bombing, but end up leaving with a better, happier impression of our peaceful city. Each visitor to Hiroshima makes it more famous than before, and each day I spend living here gives me one more spark of joy to discover, and one more reason to cherish my new hometown more than I did yesterday.

Written by the Joy in Hiroshima Team