Now & New

Life Returns to Hiroshima: Lifting the Quasi-state of Emergency

On the 7th of March, 2022, the Hiroshima Prefectural government at long last released the people and businesses from what we call 蔓延防止等重点措置 (まんえんぼうしとうじゅうてんそち – Important Measures for Preventing the Spread [of COVID-19] and Such), a mandate one step shy of a state of emergency. At a whopping nine kanji long, it’s such a long name that most locals simply dubbed it 蔓延防止 (まんえんぼうし – Infestation Prevention), or even shortened it to just 蔓防 (まんぼう – “Spreadblock”). During that period of Spreadblock, most businesses closed at 20:00, eateries suspended alcohol sales, and principal tourist attractions such as museums were closed outright. Hiroshimarians, being the resilient population that rose from the ruins of a disintegrated city, were on the whole well-disciplined among the many times the city had to partially shut down, and as a result, case numbers stayed relatively low in comparison to other major urban centers in Japan. In the days following the lifting of Spreadblock, businesses now resumed their normal hours of operation, allowing the people of Hiroshima to somewhat return to their normal lives (just with masks and hand sanitizer everywhere).

In retrospect, early March was impeccable timing to open up the city again, as the start of spring coincides with 新生活 (しんせいかつ – “shin-seikatsu”) season, a nationwide period focused on new lifestyles. As shin-seikatsu happens to be spring break for students in Japan as well as the end of the academic year, many young people in Japan graduate, enter new schools, move house, or start new jobs around this time. Stores all over Japan respond to this by marking down prices on furniture, home appliances, clothes, foodstuffs, you name it, making March and April a prime time for binge shopping, even if you’re not starting a new life. I took it upon myself to investigate the post-Spreadblock state of a couple of popular locales downtown and in the suburbs, primarily museums. In particular, as the awakening of Hiroshima now reminded me of the city’s reconstruction after 1945, I knew exactly which museum I wanted to prioritize.

Mowed Down but Grown Up

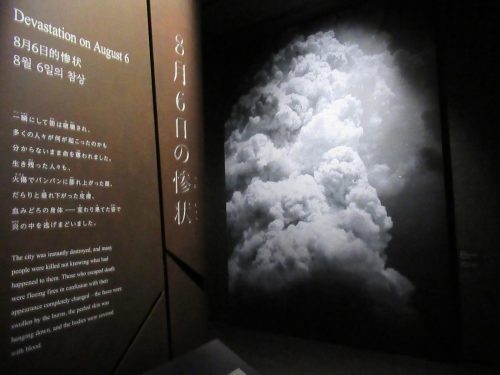

For better or worse, one cannot simply mention Hiroshima without mentioning the atomic bombing, and one cannot simply visit Hiroshima without stopping by the Peace Memorial Museum. The admission fee is a bargain, and the museum only takes a few hours to see from start to finish. Past the entrance pictured above is a room with a model of Hiroshima City from back then, with a projection simulating the instantaneous destruction of the city center in the blink of an eye. The exhibit continues with a collection of photos and items detailing descriptive personal accounts of people caught up in the blast and its aftereffects. Like so many of the photographers quoted in this museum, I too found it hard to take pictures of such gruesome sights; the billowing cloud below is one of few things I felt I could snap in good conscience.

The titles of different sections of the museum are given in Japanese, English, Chinese, and Korean, with printed descriptions in Japanese and English. The same information in other languages can be read on a touch screen panel beneath the placard: languages currently available include Simplified Chinese, Traditional Chinese, Korean, Spanish, French, Portuguese, German, Thai, Russian, Filipino, Indonesian, Hindi, Arabic, Italian, Malaysian, Urdu, and Japanese Sign Language. Some of the realia featured in the museum are architecture deformed by the blast, glass bottles fused together from the intense heat, and the belongings of the victims who perished from the detonation or passed away in the following years from aftereffects. There are direct quotes of people’s last words and diary entries citing their struggles with radiation-related illnesses. All this information serves to provide a necessary human perspective on the atomic bombing incident besides the facts, and I implore visitors to stop to read as much as they can.

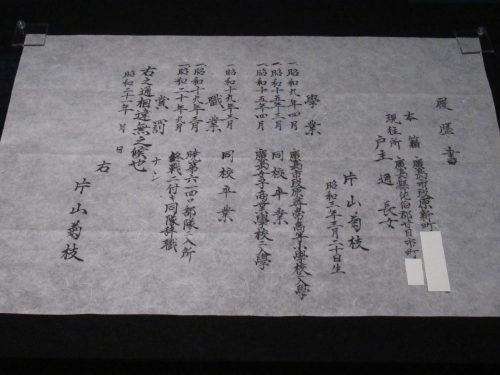

Of particular interest to me was this résumé written by a woman who wanted to get a job after the bombing, but died before she could submit it to anybody. Have you ever hand-written a résumé before? Despite Japan moving on with the times and using printed and electronic documents, some companies out there are still old-fashioned, so I too have had the displeasure of going through this laborious task. However, at least I was able to get dedicated résumé paper from a convenience store with a template structured similarly to the document above. To see the toils of a woman whose shin-seikatsu was denied go to waste was probably the most disheartening segment of the entire exhibit for me.

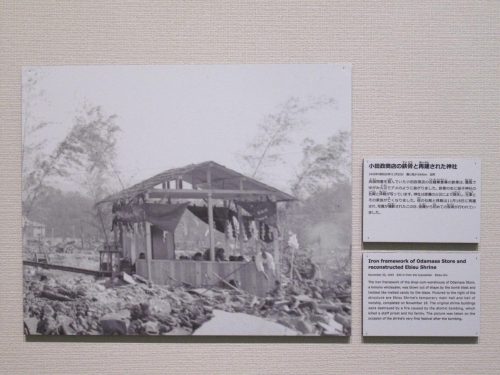

Further along are some models of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Atomic Bomb Dome before and after the blast, other items warped by the detonation, and a wall full of pictures, placards, and videos outlining the history of nuclear arms beyond the Hiroshima incident. Though everything here is available for public viewing, the touching of hands-on objects is still forbidden for the time being until this pandemic comes to a halt. As visitors approach the end of the museum, they will go down the stairs to the first floor, where the gift shop and a temporary gallery await. The theme of the photo exhibit at the time was “Living in the Rubble,” which illustrated the appearance and livelihoods of people living in a city that was mowed down not too long ago, but gradually growing back into the core city it had been. Below is a picture of a reconstructed Ebisu Shrine; there has been an Ebisu Festival here every November for time immemorial, and even in the same year Hiroshima was obliterated, citizens adamant about resuming their shin-seikatsu were able to do so at the festival that autumn.

The Prefecture’s Canvas

Just a few blocks north of Hatchobori lies the Hiroshima Prefectural Art Museum, one of the city’s primary galleries that is connected to our beloved Shukkeien. This facility wasn’t around at the time of the bombing, but the history of this art museum is tied to the catastrophe. Back then, the main venue for artists based in Hiroshima to showcase their works was the Industrial Promotion Hall, which would later become the Atomic Bomb Dome. When that building was destroyed and left in its rugged state, there was a demand for a new place where residents of Hiroshima Prefecture could appreciate the fine arts, so schools all over the prefecture started raising money to build a new museum. Following the success of the fundraiser, the Hiroshima Prefectural Art Museum opened its doors on September 22nd, 1968, and save for a few years of refurbishment, has been wowing visitors from all over the prefecture, the nation, and the globe ever since.

This museum’s collection doesn’t display all kinds of art, but specializes in pieces by Hiroshima-based artists as well as other Japanese and Asian works, specifically those made in the 1920s and 1930s. The welcome gallery segment featured several Western-style paintings accompanied by three-dimensional commentary in the form of blocks suspended by wires. Did you know that Hiroshima Prefecture has long since been known for having lots of citizens who emigrate abroad? According to the description of this piece, the painter in question moved to the United States to further his art career before returning to Japan, and the milkmaid in this picture is an allegory to that brutal-but-crucial struggle people undergo in hopes of making it big. It’s a message that hits extremely close to home, as I too took a bit of a gamble in moving to Japan; my past self probably wouldn’t have believed that I’d one day be contributing to a Hiroshima travel blog!

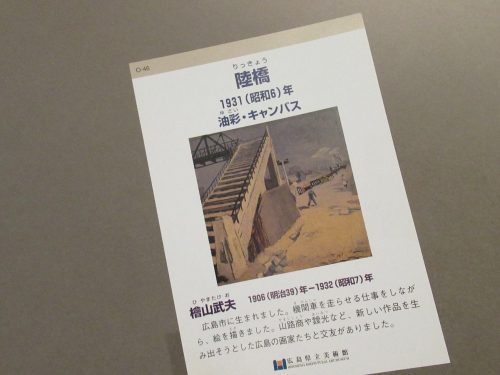

Before every gallery in the exhibit was a section filled with flyers detailing what the viewer was about to see. On the front side was information about the artist behind the piece, and on the backs of some flyers was a space where visitors were asked to write down their impressions of the works while viewing them. For instance, my initial reaction to this scene of a bridge in Hiroshima City was that it felt familiar, and I could’ve sworn I’ve seen this exact bridge in the city despite it being from the Showa era, and most likely no longer around. I walked through four rooms of phenomenal artwork spanning multiple decades, constantly seeing bigwig names like Genso Okuda, Ikuo Hirayama, and even Pablo Picasso! As my ticket to the museum came with a coupon to be used on a drink in the tearoom, after I finished viewing the exhibit, I made my way upstairs for a light lunch.

The tearoom on the third floor mostly serves light fare like pasta in addition to cakes and beverages, but I decided on something a little more out of the ordinary: cheese toast with a side of warm veggies, a cup of soup, and a glass of apple juice. It wasn’t so substantial, but the rich cheese packed a punch, and the vegetables were accentuated by the bacon bits sprinkled on top. The meager portion also meant I had plenty of room for dessert, so I presented my coupon for a discount on a lemon soda float. I took my sweet time (no pun intended) sipping and indulging in my ice cream as I took in a sublime view of Shukkeien from my seat. Plum blossoms were in season, and with the plum grove being right by the museum in plain sight from where I was, I must say that late February to early March is easily the best time of year to have a meal here.

Budding Blossoms

Of course, it’s nowhere near good enough to simply stare at the flowers on the trees, so following my lunch, I went downstairs and walked out the back into Shukkeien to get up close with the plums. The last time I was here, the plum trees had already started bearing fruit, signifying a huge contrast between coming in March versus coming in April. Plum blossoms are one of few flowers that bloom in winter, so while a considerable number of trees in Shukkeien were bare today, plum trees were able to steal the spotlight. They’re usually white (like the flowers at the top of the page) or a light pink (not unlike cherry blossoms), but some can even be a deep shade of red.

While I was strolling about the garden grounds, I kept seeing groups of young women in elegant furisode posing for photos all over Shukkeien. It turns out they happened to be students who just graduated from university and came to take commemorative photos. In spite of how numerous and perky they were, I appreciate their consideration in keeping their volume down and donning masks whenever they passed by strangers like yours truly. Their colorful garb helped add new life to an otherwise drab winter scene, which in turn enhanced my garden-viewing experience today.

Moment of Joy: The Early Tree Gets the Bee

Although cherry blossoms typically open up in late March, the Kawazu cultivar was already in bloom at this time, with bees raring to pollinate. Sakura season had yet to officially begin, but it paid off to be an early bird if it meant seeing both plums and cherries at the same time. Considering how I was able to witness two famous flowers simultaneously in one garden, coupled with the release from Spreadblock, I honestly couldn’t have asked for a better window of time to drop by Shukkeien in the spring. If these clusters of pink beauties don’t scream shin-seikatsu, I don’t know what does.

Giving Life by Saving Lives

My final stop on this citywide investigation of reopened museums took me up north to Chorakuji, home of the Numaji Transportation Museum. I made sure to ride the Astram Line up there for a discount on admission, and deliberately chose to visit on a Saturday, when shows and workshops are planned. The theme of the special exhibit this time around was rescue teams, so a dedicated space on the second floor was filled with equipment used by the fire department, police, and the Japan Coast Guard, as well as promotional videos highlighting their training exercises. On one end, visitors learn about how pulleys make it easier to lift heavy things with less input from the user, and can even try out the Chain Block, a device that makes transporting 35 kilograms so easy, even a child can do it. In contrast, the other pulleys make it nigh impossible to lift the same weight, so don’t try too hard with those, lest you hurt yourself.

At another corner, a rescue worker demonstrates on video how to tie a knot that’s critical for his harness when descending to assist people in danger. Provided on the tables are lengths of twine, which aren’t quite the same as the rope he was using, and might have made following his instructions a little more difficult, but at least the concept was still the same. A museum employee saw me struggling to grasp the steps and offered to tie the knot alongside me, and although her example helped me understand a smidgen better, I still had trouble keeping up with the pace of the video. Eventually, I somehow managed to make a knot that somewhat resembled the one in the video, so I called it quits there.

For a more immersive insight into what it’s like to rescue somebody, they had a virtual reality type of video set up by the entrance to the special exhibit featuring two workers practicing abseiling techniques. The video was shot from the point of view of one such worker with a 360-degree camera, so visitors can use the buttons on the panel below the screen to look up, down, and all around while the men abseiled down the side of the building. Viewers can gain a sense of serenity from the blue sky above, a sense of fear from looking straight down at the ground below, or a sense of bewilderment at the flawless form and speed of the adjacent man abseiling. I myself have abseiled before, and as I realize it takes a strong core and a lot of guts, I tip my hat to any man or woman who can do something that daring any day of the week.

As my ticket allowed re-entry for the entire day, I popped out to grab lunch in another part of town before returning to catch a science show on the first floor, free of charge. The show–which is aimed at small children–was pretty bare bones in the objects used, and focused on the oft overlooked potential of aerodynamics. Tricks ranged from toppling a sheet of paper with one hand but not the other, to seemingly defying the laws of physics with a hair dryer. Nothing too fancy, but the young tykes got a kick out of all the demonstrations, and even a grown-up such as myself managed to learn a thing or two about air power.

Following the conclusion of the show, I wrote my thoughts on a survey and submitted it to the staff, then walked outside to witness children with their families taking the battery-powered cars and wacky bikes out for a spin. Those who chose to play with these vehicles outdoors certainly picked the right day as the weather was optimal, and I myself was tempted to try riding too, but then figured that simply watching others would be entertaining enough. The sight of both kids and adults trying to figure out the contraptions was rather humorous, but upon reaching the end of the wacky bike course, my eyes were directed to a vehicle of a different nature. This seemingly normal number 3 streetcar was actually exposed to the atomic bomb, and on select days (unfortunately not today), the Numaji Transportation Museum lets the public see the interior. It was at this moment that something dawned on me regarding all the museums I had seen this week, and in my mind, I was taken back to 1945.

Everywhere I went in Hiroshima had some connection to the atomic bombing: Peace Memorial Park was ground zero, the Prefectural Art Museum was the replacement gallery that revitalized art appreciation, Shukkeien was host to people and a tree or two that survived the blast, and even the distant Numaji Transportation Museum preserved relics from Hiroshima at that point in time. The concept of the atomic bombing is inescapable because it’s such an integral part of the Hiroshimarian identity, and the new lives that sprung up from the rubble are a testament to the city’s resilience. Back then and even now, the stalwart residents of Hiroshima have repeatedly demonstrated their willingness to rise above any crisis and keep their peaceful city alive by any means necessary. We all played our part to save lives during Spreadblock, and as a result, the city feels more alive than it has been in a long while. Though COVID-19 and the bitter memories it brought may never vanish from this Earth, it is our collective responsibility to make the best of our shin-seikatsu and make Hiroshima an ever more livable city in the eras to come.

Written by Kevin Peng